In December of 2018, Google’s CEO, Sundar Pichai, was asked a set of questions by the United States Congress. His responses left… a lot… to be desired.

Thankfully, when I told friends from clickstream data provider Jumpshot about this, they were able to send me numbers that give far better answers to Congress and the American people (at least those who find their way to this post) than what Mr. Pichai provided.

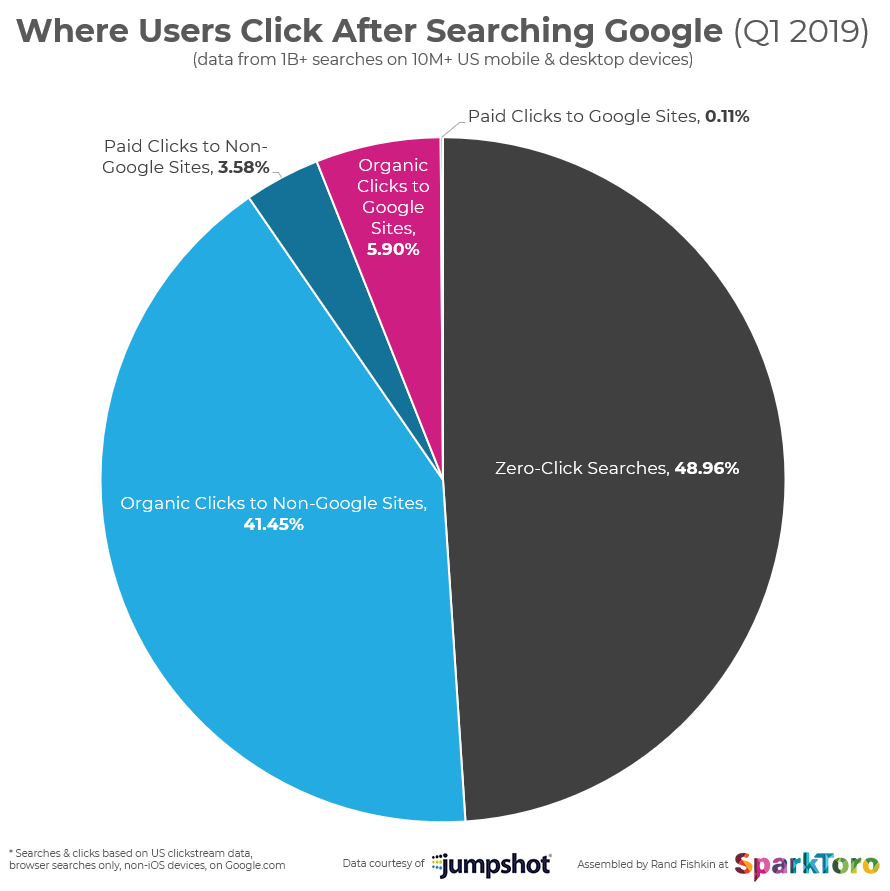

According to Jumpshot*, in Q1 2019 Google’s US web search engine:

- Received 150+ Billion searches

- Solved 48.96% of those searches without a click

- Sent 7.2% of all search clicks to paid results

- Sent 6.01% of all searches (~12% of search clicks) to websites owned by Alphabet, Google’s parent company

- Directed a click to non-Alphabet-owned websites (aka, the rest of the web) after 45.03% queries

Those aren’t perfect answers to Congress’ questions, but they’re way closer than what Google delivered. And, if looking at them makes you feel like things are rough for web creators, publishers, and marketers focused on organic search traffic, you’re not alone. But, keep reading. There’s some light at the end of this tunnel.

Below, I’ve made a chart showing a visual look at what happens after searchers performed a browser-based query on Google.com in the US last quarter.

This visual’s data is inclusive of both desktop and mobile searches. It shows that despite the rise of both zero-click searches and paid search clicks (covered in more detail below), organic search clicks are still very much alive. In fact, for every click on a paid result in Google, there are 11.6 clicks to organic results. SEO is far from dead.

In the past, my analyses of Google’s Click Through Rates (CTRs) have failed to include a crucial element that I’m adding here: clicks back to Google’s own properties.

The data tells us that 6.01% of all searches (~12% of all clicks) end in a click from Google… right back to another Google owned property. Here’s a list of all the domains I asked Jumpshot to include:

- *.google.com (including, but not limited to all of the below)

- maps.google.com

- sites.google.com

- news.google.com

- domains.google.com

- store.google.com

- play.google.com

- chrome.google.com

- blog.google.com

- analytics.google.com

- drive.google.com

- images.google.com

- support.google.com

- plus.google.com (before it was retired)

- *.youtube.com

- .google (Google’s top-level domain extension)

- *.gmail.com

- *.android.com

- *.abc.xyz

- *.waymo.com

- *.nest.com

- *.blogger.com

- *.thinkwithgoogle.com

- *.waze.com

- *.orkut.com

- *.withgoogle.com

- *.google.org

- *.googleblog.com

- *.googlefiber.net

- *.campus.co

- *.googlesciencefair.com

Most of those receive a very small amount of Google’s overall search traffic. Android.com, for example, while a powerful part of Google/Alphabet’s product suite, only received ~0.01% of all search clicks. YouTube on the other hand, received more than 6% of desktop search clicks**!

Good news: over the last three years, Google’s sent a fluctuating, but fairly flat amount of traffic back to their own properties. They’re not cannibalizing an ever-increasing portion of their own searches (a fear myself, and many marketers had).

Bad news: In Q1 2019, Google directed nearly 12% of all search clicks back to Alphabet-owned properties, an absolutely mammoth amount. And Google already solves half of all searches without any clicks at all.

Worse news: This analysis is missing one key piece — searches ending in a click to a Google-owned app on a mobile device (YouTube, Gmail, Google Maps, etc). This is due to how Jumpshot gets clickstream data from browsers and almost certainly means an even greater proportion than 12% of searches are sent by Google back to Alphabet properties. Yikes.

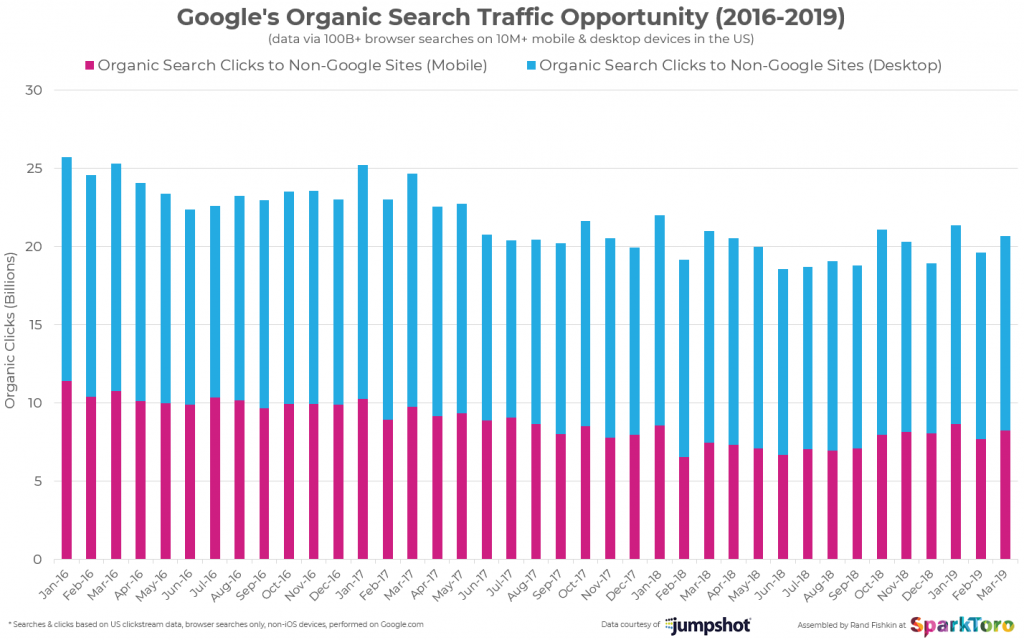

The feeling that there are fewer clicks available for publishers and websites to capture is clearly observable in the numbers over time.

I’ve broken out mobile (in pink) and desktop (in blue) to help illustrate where opportunity is shrinking. Not surprisingly, it’s true on both types of devices, but far more rapid on mobile, where Google’s aggressive SERP features and instant answers have come to dominate numerous results.

By Jumpshot’s estimate, there were ~75.6 Billion organic, browser-based search clicks available from Google in the US in Q1 2016. Three years later, than number is ~61.5 Billion. In 2019 Google sent ~20% fewer organic clicks via browser searches than they did in 2016.

It’s almost certainly true that non-browser-based searches like those in Google’s mobile search app, the Google Maps mobile app, Google Home, Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, and others, also have large amounts of search volume, but… how much traffic they send to websites is hard to say.

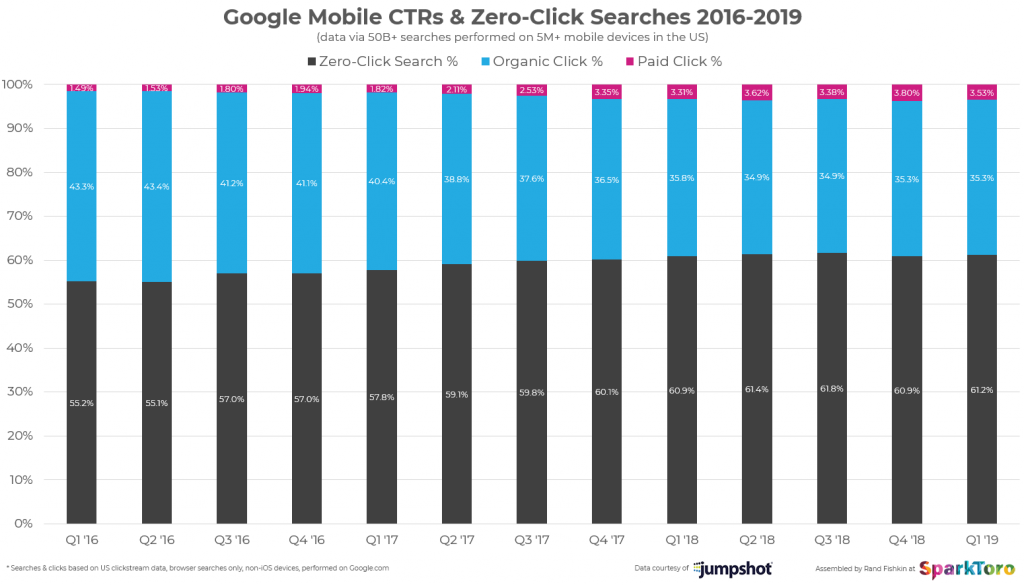

What we know is that over the last three years, in browser-based searches, Google has grown the CTR of paid clicks by more than 75%. They’ve grown the percent of queries with zero-clicks by almost 12%. And, as a result, the organic CTR has dropped by more than 13% to 47.4%.

Desktop (as seen below) is accounting for only a small portion of that drop.

Mobile (as seen below) is responsible for the lion’s share of growth to paid, growth in zero-click searches, and the drop in organic.

All together, this data’s telling a narrative of loss, but only in one metric: percent of search traffic going to organic clicks. The reasons I’m still very hopeful and optimistic about SEO are:

- Google is still growing! Desktop and mobile browser activity have largely plateaued, but mobile app search has almost certainly compensated for more than this relatively small decline the past three years.

- That means there are probably MORE total searches, and MORE total traffic available than three years ago, and definitely more than 5, 7, or 10 years ago.

- A search ending in zero-clicks is not useless to marketers or publishers. Yes, the metrics are harder to track and the ability to convert a visitor to take action is reduced, but the ability to influence that searcher still very much exists. For that reason, I think we’ll see a huge rise in demand and services for On-SERP SEO, the practice of optimizing the results page in Google to deliver the message a publisher, brand, or organization desires.

- I think Google’s going to be relatively cautious about increasing the percent of traffic they send back to their own properties given the upcoming US Dept. of Justice investigation into whether they’ve violated antitrust regulations.

- The press is holding Google’s feet to the fire a little more than they have in years past, and that pressure will also help keep the search giant’s self-promotional proclivities in check.

All that said, I think fear about where Google’s search traffic goes is entirely reasonable. Google has more than 94% of the US search market, they send more than 10X as much traffic as the next leading referrer on the web (Facebook), dominate the online advertising market (with 38% of all digital ad revenue to Facebook’s 22%), and control (perhaps to a dangerous degree) the livelihoods of millions of small business owners, startups, publishers, and web creators. A skeptical, watchful eye over such a powerful beast is certainly needed.

*Postscript on Jumpshot’s methodology: Jumpshot collects billions of searches every month from more than 100 million devices around the world, including 10M+ in the US (the basis for the data here). However, this data does not include any iOS devices, and is limited to activity in mobile and desktop browsers. This means searches that happen in apps, like the Google mobile Search app (which mostly, but not perfectly mimics mobile, browser-based search) are not accounted for, and would further add to these totals. Also excluded are searches that occur on voice-only devices like Google Home or Amazon’s Alexa.

**Postscript on YouTube Desktop vs. Mobile: Because Jumpshot’s clickstream data doesn’t track clicks that open an app (like the YouTube app, installed on nearly every Android device in the US), I’ve reported desktop numbers. My friends over at Jumpshot tell me they’re looking into the clicks that open or send the user to a mobile app, and we may have that data to share in the future.