For 25 years, links have been core to how Google ranks web pages. But, today, I think most marketers dramatically overestimate their importance. There’s good evidence that over the long run, links won’t be all that crucial to Google’s rankings, and will be replaced by lexical references that connect topics and keywords to a brand, website, or page—what I’ll call “inferred links.”

When Google crawls the link in the bullet point below, they can follow it to the destination webpage.

- Check out Pendleton’s selection of men’s cardigans.

That’s useful for discovery, and historically, it was often an indication of endorsement. But today, 80-90% of the time, a link on the web to a purchase-able product indicates biased motivation.

Compare that to an inferred link:

- In its price range, I don’t think there’s a better cardigan you can buy than Pendleton’s Westerley.

As a human being browsing the web, the inferred link is less convenient (I have to go to Google and search in order to find it), but almost certainly more authentic. A link takes effort to create. Text mentions require much less. Text, especially at web scale, represents how people think about the world. Links, meanwhile, usually represent a motivated, biased version of what someone wants other people to do.

Ironically enough, the most unbiased links to Pendleton’s cardigan web pages are probably nofollowed from places like Reddit and Pinterest’s fashion communities. The followed links, even the *good* ones, are the creations of financially-motivated people in publications, blogs, magazines, often influenced by PR campaigns, and SEO-focused link builders.

If you want quick and easy access between web pages, a link is great. But if you’re seeking meaningful, authentic indicators of unbiased endorsement, the inferred links are vastly superior. Google today has the ability to interpret both types—inferred and direct.

When it comes to SEO, however, 99.9% of practitioners will still take the link > the inferred link. That’s because, for the purposes of ranking better in Google’s search engine when someone types “men’s cardigan” or “Pendleton Westerley” the link still carries more value than the inferred link. Today, in 2021, perhaps it’s as much as 2X the ranking influence.

But, ten years ago, that ratio was closer to 20X or 50X. Twenty years ago, the inferred link was close to useless (at least as a raw ranking input). Is it reasonable to assume that in five years it might be 1:1? Is it possible that today, it’s close to even?

In a world where self-designing algorithms govern rankings, I don’t think we can answer these questions with precision. What we can do is better understand why, in a sophisticated machine-learning system, inferred links will almost certainly overtake their direct counterparts.

Some Background on Links & Rankings

Google’s invention was predicated on the notion that links were proxies for votes. If a page earned more votes from more important pages than its competition, it should outrank them. At least… that’s how it went in the early days. Then link analysis become more sophisticated—anchor text, trust, surrounding text, topic analysis, predictive surfer modeling, et al entered the picture.

These new techniques helped Google stay further ahead of link graph spam and manipulation than its competition, but it was an exhaustive, repetitive game of cat and mouse for their search quality and webspam teams.

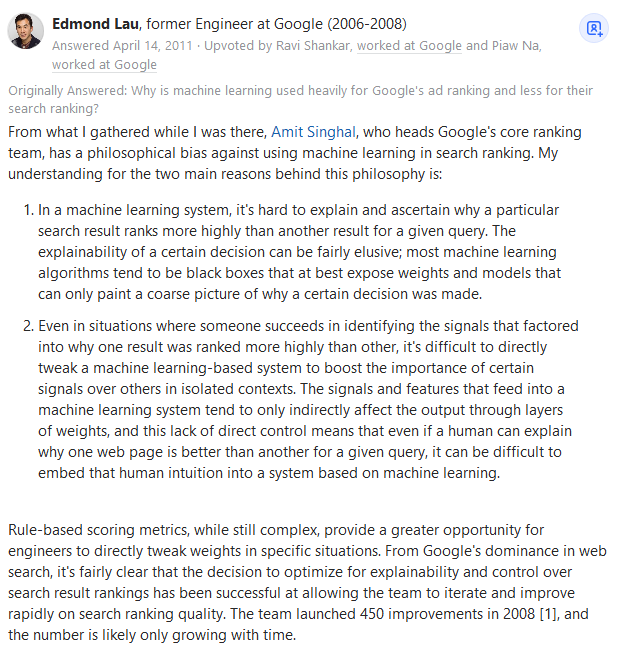

That’s because, for it’s first ~15 years of existence, Google’s algorithms were designed by committees of engineers, sitting around tables, reviewing results, and deciding when and whether to increase or decrease the importance of a particular ranking element. Up until the departure of Amit Singhal (probably to keep his sexual harassment behavior quiet more so than because of his resistance to machine learning), Google’s ranking systems were, according to invited-into-the-room sources like CNBC or Steven Levy’s In the Plex, designed by people.

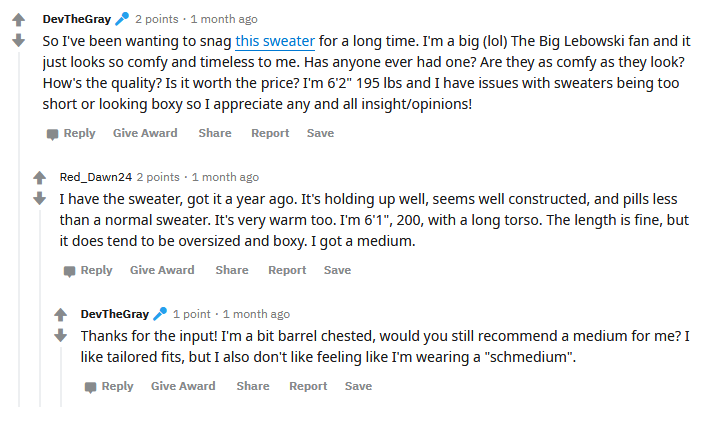

Search Engineer Edmond Lau on why Google didn’t adopt machine learning in the early years

Today, however, Google proudly talks about how its modern rankings are built by deep learning algorithms. In this model, engineers tell the systems what to optimize toward (usually measures of searcher satisfaction), and the machines decides which ranking elements to use and how/when to weight them.

If the machine’s computations determine that a model with highly-weighted links underperforms a model with higher-weighted inferred links, the learning system will automatically change the ranking weights. Supposedly, in the most advanced systems Google’s built, the machine not only determines the weighting, but also the inputs themselves, potentially discovering new ways of ranking all on its own.

Maybe it is the case that in 2021, links are still better predictors of how the ranking systems should work, and so the machine learning selection system still favors them. Maybe that will even be true for years to come.

But, I doubt it.

Why Inferred Links are Superior Endorsements

The beauty of an inferred endorsement that comes from naturally written text (on crawlable social media or web pages) is undeniable. Inferred links have:

- More scale – simply because there’s millions of times more text than links.

- More context – text can be analyzed so many ways, the only real limitations are computational power; something Google’s become excellent at solving over the past decade.

- More attribution – who wrote that piece? Where was it published? What signals of authority and expertise do the author and publisher carry? Given so many links are added post-hoc (especially in the worlds of journalism, blogging, and corporate copy), the attribution between writer/publisher and brand/concept/page connections are immensely valuable.

- More authenticity – as mentioned above, links sometimes exist out of the goodness of some author’s heart and intentions. But far more often, there’s financial motivation or SEO knowledge behind the creation or modification of a link. That’s also possible with text, but at scale, much less of the overall content graph.

In the past, the kinds of sophisticated, nuanced analysis necessary to make an inferred link superior to a direct link were lacking. Today, they exist. In the future, they’ll get better, cheaper, and faster. Even if links rule today, I can’t see that model lasting much longer.

Steelmanning the Case for Inferred Links

Yesterday, I tweeted a preview of this theory and got some superb feedback, including a few very passionate doubters. I’ll present and address those counter-arguments below.

Via Sean Dawes on Twitter

Sean argues that text mentions are more open to misinterpretation than links, and I’d agree. I think this is one of the core weaknesses of the inferred link mode and of entity/text-connections in general. But, I think this is a short-term weakness that can be solved by a combination of more data and better text analysis systems, both areas where Google loves to invest, and areas that give them a competitive advantage.

Plus, I think a world where inferred links carry similar or even more weight than direct links is never going to be a world where links don’t count at all. Links and inferred links often co-occur, and in cases where they do, patterns can be identified that helps Google determine how to interpret content that’s referencing a page even when it lacks a link or contains lexical confusion.

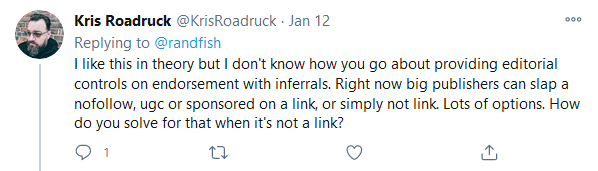

Via Kris Roadruck on Twitter

Kris makes the point that publishers don’t currently have controls to mark editorial content from potentially user-generated content or comments.

I’m not sure that’s accurate. Not all, but definitely most CMS’ have clear demarcation any search engine can recognize between editorial and user-submitted content. Also, even in the event there aren’t clear lines, the text content can still be analyzed, and Google can still separate one author from another even if there’s no code indicating that change.

Kris also points out that publishers can “nofollow” a link today in order to prevent it from passing value, but cannot “no-endorse” inferred endorsements created by mentions of a name, brand, website, or other entity and a related term/phrase.

While that’s true, I think Google (and plenty of other text analysis systems) are nearly at the point where they can separate a positive mention and association from a negative one, and an endorsement from a mention. They can decide that when a well-followed, noteworthy expert in a field tweets about a topic, it should carry more weight than a dozen or a hundred anonymous Twitter accounts do likewise.

For example, the phrase “Pendleton makes cardigans,” on this web page about Google’s rankings is even now being scanned and analyzed by the search giant’s crawlers. They’ve likely determined it to be off-topic, and not particularly worth counting toward the retailer’s rankings for the query, “cardigans.” But all those Reddit threads about cardigan recommendations? Yeah, Google knows those are solid endorsements.

Via Jennifer Barry on Twitter

Jennifer makes the good point that brands and websites would, ideally, want links to exist because it makes navigation easier. She’s absolutely right.

But, I believe that’s orthogonal to Google’s interests about what to rank. They don’t particularly need (or even necessarily want) web users to follow links. Google, conveniently enough, is probably the beneficiary of all those link-lacking text endorsements across the web. When someone sees a mention of Pendleton’s cardigans without a link, what do they do? Search Google.

Via Busta Cloud on Twitter

Busta’s point is that larger players with well-known brands will get a competitive advantage from a move like this. Presumably, he’s suggesting that today, link building can still be done by creative, smaller businesses, while brand mentions and associations in text are out of reach.

I’d argue that links are just as prohibitively powerful as moats for big brands, and that small and new companies have just as much trouble competing on one as the other. I’ve also seen plenty of evidence that Google doesn’t just count total links or mentions, they look at the rate of acquisition and conversation. Today, Pendleton might be a great match for cardigan related searches, but if, over the next 60 days, there’s a huge amount of buzz about a new brand, they might well overtake Pendleton in the rankings, even if their inferred (and direct) link all-time total is 1% that of their long-standing competitor.

What Should Marketers Do?

I’m not suggesting we stop link building entirely. It’s probably still worthwhile, and in some sectors, it may be the case that Google’s machine learning systems still prefer links to inferred links by a weighting of 2, 5, even 10:1.

But I worry about how modern marketers prioritize earning links over earning mentions, endorsements, and brand coverage. If you pay an SEO agency to get you 50 “high quality links” a month for $5,000, and refuse to pay a digital PR agency to get you 10 mentions in relevant publications for the same price, I’d argue you’re making a very unwise tradeoff.

Brand mentions, especially relevant ones in publications that actually reach your audience don’t just impact keyword rankings. They drive branded search traffic. They improve brand awareness. They almost always increase conversion rate among the audiences they attract. And much of the time, ironically enough, they indirectly lead to more links than link building!

That podcast you appeared on? They probably linked to you. That industry publication that covered your launch? They probably did, too. That social media campaign that got all the buzz? It undoubtedly led to links. That mention in the New York Times that failed to link to you? It’s highly likely that niche publications will be more likely to write about AND link to you because of it.

So here’s my proposal: stop treating brand coverage, mentions, and inferred links like garbage. Start assuming it counts. Measure it. Track it. See if brand-focused, digital PR campaigns bring as much or more than keyword-ranking-focused SEO link building campaigns. Until you have some data, you’ll never know, and you’ll never be able to effectively allocate marketing spend & effort.

For more discussion on this topic, including some fascinating examples and counter-examples, check out the original Twitter thread. And, as always, if you’ve got stories to share or critiques to make, I’d love to hear ’em in the comments.