Ever wonder why so many business software companies make it so darn difficult to start using their products? Or why subscription-focused tools are so obsessed with making it hard to quit vs. making it easy to sign up? Why don’t these SaaS (software-as-a-service, aka subscription) companies want customers who might only need their product every few months or even only once each year or two?

Incentives. Specifically, the incentives around how their businesses get valued by investors or potential buyers.

99% of subscription businesses, whether they’re selling customer service software or marketing research tools or video-calling apps, are trying to do one of two things:

- Raise money from institutional investors (i.e. VCs and the ecosystem of angels + seed funds around them)

- Get acquired by companies who’ve raised VC and/or plan to IPO

These investors value predictable growth, and they’re willing to pay a premium for companies that can show low “revenue churn.” That is, they ideally want every credit card that paid money last month to pay as much or more money next month.

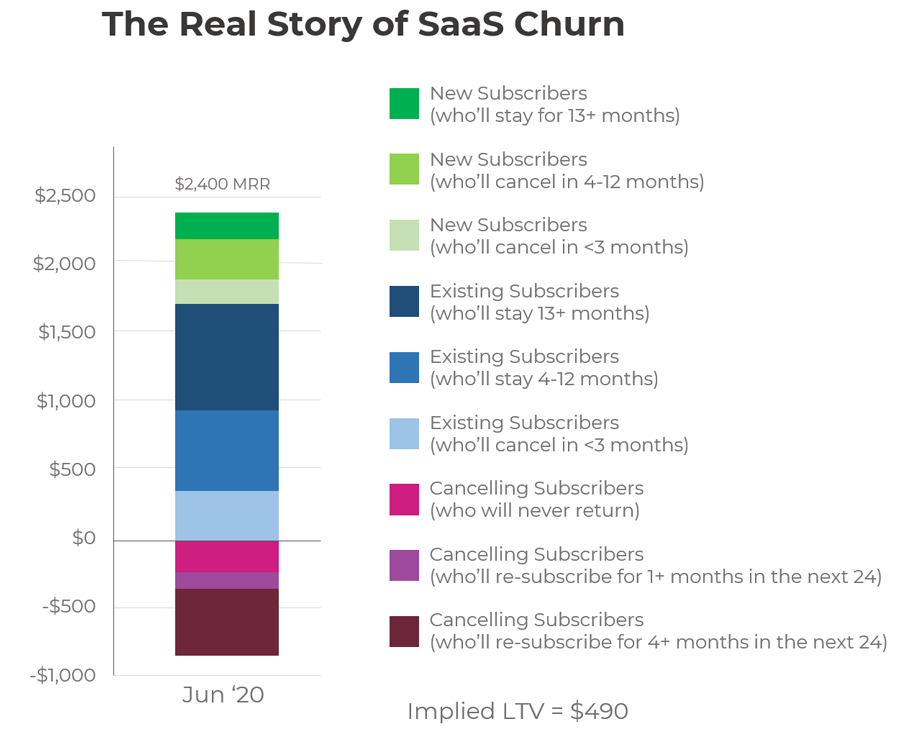

A churn graph with pink bars like this is incredibly scary to investors and acquirers, but maybe it shouldn’t be all that scary to founders (or customers)

There are some logical reasons behind this, including:

- It’s great to have predictable income, so you can make long-term expense and profit budgets without much stress

- Low revenue churn is a signal your product is very difficult to live without (which suggests that even if things in the broader economy or with your market get rough in the future, you’ll probably still keep a lot of your customers)

- If you’ve got low churn, every new subscriber is likely to be with you for a long time, so you don’t have to spend big efforts on marketing to keep growing

- You can spend more money on paid acquisition to get new customers knowing that lifetime value (a problematic phrase I’ll circle back to later on) is relatively high

SaaS investors (especially in the VC world) like to call high-churn subscription businesses “leaky buckets.” The analogy being that each month, you’ve got to refill the bucket because you’re bleeding (they *always* use that word, “bleeding”) customers. Wouldn’t it be so much better to plug the holes by making the product “stickier” (this word is also required; woe be to the subscription business that does not heed these in-crowd linguistic indicators)?

When a subscription business has too high a churn rate, investors ignore them, markets devalue them, and boards of directors panic. But, pssttt… I’ll let you in on a secret: customers don’t give a #%$&.

In fact, as a customer, it’s really nice to know that cancelling is easy, lots of people do it without hassle, and I can use your product for as long or short as I need. It’s also great knowing I can sign up without a lengthy contract or a pre-qualification sales pitch or a long series of interactions with customer success professionals whose actual job is to make sure I’m not a “churn risk.” It’s convenient to only pay for a product when I’m actually using it, and not suffer any particular pain when I stop paying for a few months or even a year or two.

If those things were broadly true across the SaaS world, I know for certain I’d have signed up for at least a dozen products in the last 2 years that I’ve instead opted to avoid. Services like Pitchbook, SimilarWeb, Zoom, Crunchbase, Canva, Medium, and more. By that same token, I’ve been easily sucked into product like Wistia, Hotjar, Buzzsumo, Mailchimp, and others because it’s easy to sign-up and one-click to cancel.

Canva’s pricing page says I can “cancel anytime during my trial,” but there’s no indication of how hard it might be after that, so I never made it to the next step.

But, individual examples aren’t the point here, incentives are.

Whether you’re 100% on-board with the investment world’s thesis that revenue churn is a company-killer or somewhat skeptical (like me), it’s clear that this mentality has a huge effect on the entrepreneurial world. The desperate need for low-churn pervades every aspect of SaaS, including which businesses get started and which problems get addressed. As a result, thousands of painful problems and useful solutions are completely dismissed by almost every would-be SaaS entrepreneur simply because they’re one-time or short-term.

No founder wants to intentionally build a product that might have high churn or deliver too much value upfront. And that sucks for potential customers who wish the frustrating problems they face only once or twice a year could be addressed with as much gusto as those they face every month.

The good news is that whenever a category or type of problem is underinvested, competition is minimal and hungry customers are plentiful.

I feel certain that in SaaS, there’s a metric ton of opportunity for founders willing to give the finger to the exit/next-VC-round focused world and build something a lot of people want: software that’s useful every time you pay for it, but neither painful nor difficult to cancel.

For example, I recently helped an entrepreneur working on their startup’s market competition slides for a fundraising effort. This founder emailed to ask if I had a subscription to Pitchbook, a common research tool in the competitive intelligence world. I don’t. So I poked around the Google search results for pitchbook pricing. Ugh. What a mess.

Best I can tell, Pitchbook costs ~$20,000/year, though depending on who you are and what you’re doing with it, there’s stories about how their sales team gives either deep discounts or jacks up the rates. It’s tough to tell whether those are accurate, from the earlier days of the company, or still an issue, but regardless, it’s no fun trying to sort out.

Dammit Pitchbook! Just tell me how much you cost and let me sign up for a month. Do you really hate getting money so much you’d rather turn away 50 short-term signups to get 1 long-term subscriber? What’s up with that?

Here’s what’s up: Behind the scenes, Pitchbook’s owner, Morningstar, almost certainly wants predictable, low-churn revenue more so than total revenue or profit. Before they were acquired, the same would have been true of Pitchbook’s investors and potential future investors. They’re happy to give up hundreds or thousands of potential short-term buyers of their product so they can show “low churn” numbers in the metrics.

Given this infuriating model, that PPC ad for Mergr looks mighty tempting.

Unfortunately, after poking around Mergr’s site, it appears the product isn’t built for the kind of startup-market analysis my friend wants to do.

Services that are not just easy to cancel, but painless to lose and easy to return-to have some significant, underappreciated advantages as a buyer, namely:

- It’s a great cost savings to cancel and re-subscribe at will

- No extensive setup or sales process means low-friction transactions

- These services are easy to bill directly to clients (if you’re an agency or consultant doing work on their behalf)

- No need to sweat if the service is turned off or has downtime

- I don’t want more subscriptions I *can’t live without*. I want more subscriptions that are fantastically useful, but non-essential to my company’s operations.

I’ve been wracking my brain to come up with drawbacks, but the only ones I can come up with are on the product provider’s end. Easy-to-cancel likely means the product isn’t of life-and-death importance or key to making your business (or personal life, for B2C subscriptions) run. If you’re an investor who wants to only put money behind companies that might become “unicorns,” these are drawbacks. For everyone else…

Let’s go back to that graph I showed of churn rates over time. Predictable, recurring income is an undeniably terrific asset, but in all my years of SaaS operations, the real story of churn (and of true “lifetime value”) is much more nuanced than the average subscription length across accounts.

The real story is that, whether you’ve got a high churn product, a low churn one, or something in-between, actual customer behavior is way more complex than what cancels + renewals show. Some folks who cancel will subscribe again. Some of those who do will do so under a different name, email, credit card, and company. Some who cancel did so because they were promoted, and they’ll tell their new reports or old team to re-subscribe at some point. And, yes, some who cancel (probably a good number) will never return to the product again.

At my last startup, we spent literal years trying to calculate true LTV based on cohorts of behavior that predicted certain churn characteristics. And then we got beaten by a non-venture-backed competitor who, at least according to their public statements, never even looked at their churn rate and just focused on product and customer experience. Doh.

Via Frank Buckler on LinkedIn

The real question subscription builders should be asking is whether they want to put all their focus on maximizing singular subscription lengths (i.e. one account that signs up with one card and stays as long as possible) or if it’s worth devoting any attention to those who might cancel and return. Or cancel and recommend.

I cannot tell you how to run your subscription business, but I can tell you how we’re thinking about this at SparkToro. I never want to treat *any* of our customers who cancel as one-time users. I want them to have a great experience signing up, using the tool, cancelling, and coming back someday.

That’s why we send this email to everyone whose account come up for renewal:

It’s why we’re extremely generous with refunds even if you miss the deadline. And why we make the cancellation process so simple (just a visit to the account page, and two clicks to cancel).

But it’s not just the design of the cancellation process that’s unique. We’re also building our product to be truly useful and valuable even if you only use it for a month or two. I look at our options like this:

- We can optimize our product to earn paying subscription from a potential customer one out of every six or twelve months

- We can build our product to be primarily valuable-to or usable-by those who stay for long, multi-year stretches

- We can be friendly to both short and long-term customers, because both are worthy of our consideration

Call me crazy, but I think #3 is absolutely the right way to go… Unless you need to raise VC. Then choose #2, and leave the other options to us Zebras 😉