Years ago, one might reasonably separate the elements of Google’s results into distinct entities: Google News, Books, Videos, Images, Local… But today it’s near-impossible. The list of elements Google might show for a given query are so vast and varied that at the macro-level there’s really only three kinds of search results that matter:

1) Google-owned properties and answers (where earning traffic to one’s own website is difficult or impossible)

2) Paid results (those that come via Google’s advertising programs)

3) Organic, web listings (where earning traffic directly, or almost-directly to a third-party site *is* possible)

In Part 1 of this series, I covered Google’s own dominance of many rankings and in Part 2, talked about paid ads. In this piece, let’s discuss the final element: organic listings, those seemingly rare results in Google that can still, directly send traffic to a website not owned by the search monopolist.

So, what’s the secret to ranking #1 in these traffic-sending, unpaid results?

Engagement.

If your content results in higher engagement metrics than any other, especially if it does so either A) consistently over time for a significant portion of searchers or B) temporarily because of a spike in searches seeking your particular content, it will rise to the top of the non-paid results.

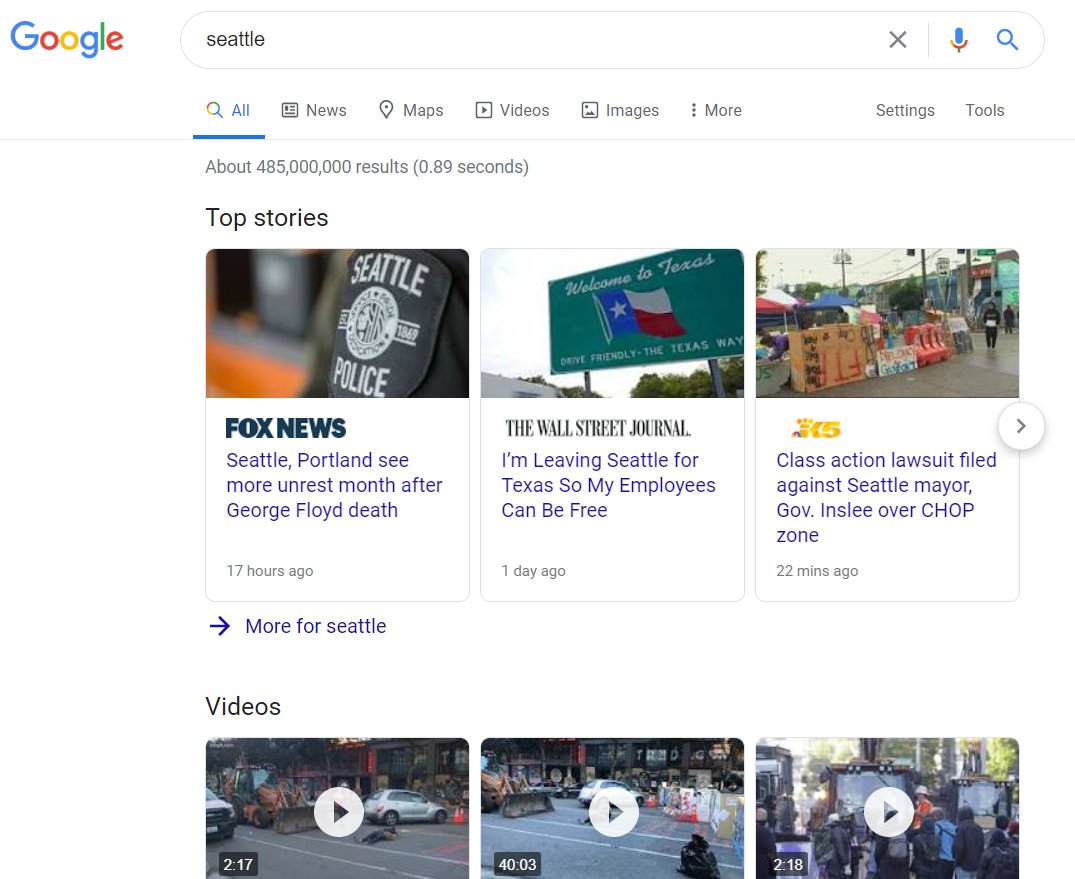

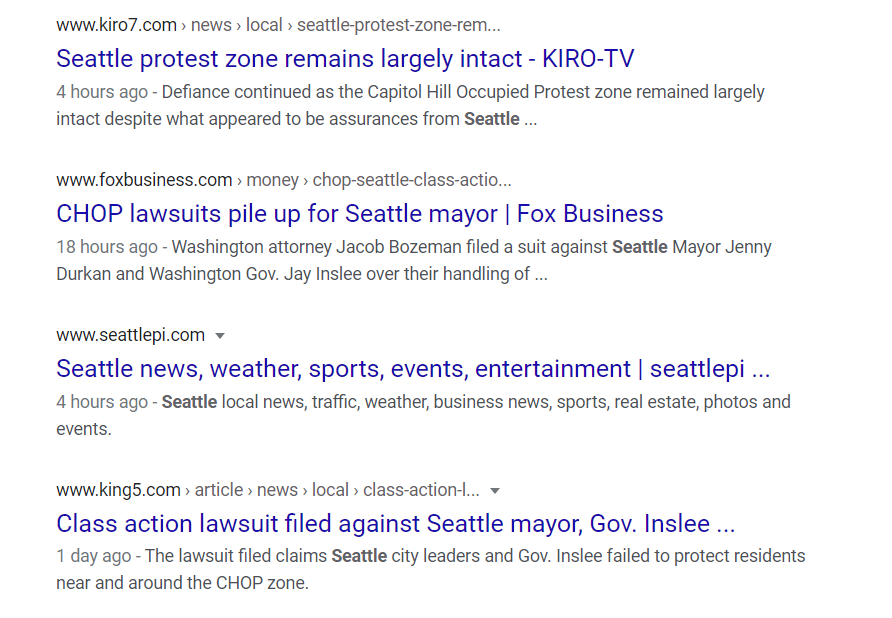

I illustrated this recently on Twitter with a search for the city of “Seattle,” a search that historically produced results like the tourism-focused VisitSeattle.org, the City of Seattle’s official government website, and the Seattle Wikipedia page. But searchers don’t want those results right now. There’s an entirely new group of searchers for the city name, and they want something very different from what past searchers sought.

Why is query volume for “Seattle” spiking? Because a number of right-wing news sources, online and off, are publishing news that stirs up fear, anger, and political conflict about a 6-block section of the city (incidentally, right outside my old apartment).

Over the last couple weeks, Fox News, in particular (a popular conservative TV network) has covered the area’s lack of policing with sensationalized and often-misleading (if not outright fictitious) stories. And during that same period, Fox’s website, or those affiliated with it, has almost always been on the first page of both news results and web listings.

My politics should be well known to readers of this blog by now, but politics isn’t the point here. Google’s rankings are. And this search is a superb example of how Google delivers what these conservative-driven searchers want, all other signals aside. But, it’s far from the only one.

When controversial topics spike in popularity and search volume, Google’s ranking systems respond in a number of ways:

1) The algorithm considers which types of content blocks to feature and where, potentially displacing web listings in favor of news results, images, videos, etc. (or the inverse).2) Web listings in particular become more diverse, highlighting newly relevant results. Consider what happened when”Corona” searches switched from being primarily about beer to primarily about a pandemic. Or, more confusingly for Google, the query “Juice,” which tries to balance results about a beverage, several songs, a film, a band, and more.3) Google’s “Query Deserves Freshness” (QDF) elements kick in, both as triggers of these shifts and as a potentially-useful filter for the results, highlighting more recent content over more authoritative (i.e. well-linked-to and engaged-with historically) works.

All of these use forms of engagement to trigger and to respond. Unfortunately, many web marketers, even those deep in the field of Search Engine Optimization (SEO) are generally hesitant or even outright dismissive of engagement signals in Google’s rankings. I think this stems mostly from Google’s own representatives, who frequently make claims that various individual signals connected to engagement (like a blanket click-through-rate or raw clicks themselves or bounce rate in Google Analytics) aren’t used.

Historically, I was able to prove the use of these signals in a series of live experiments. Since the 2013-2015 era, Google’s evolved and these types of simplistic calls to search+click at events and on Twitter haven’t worked as well. But, pick nearly any trending topic in the news or on social media, and you’ll witness Google’s rapid reaction to shifting searcher demand. Follow slower, but-still-evolving queries with changing searcher demand patterns and you can see it in non-current-events issues, too.

The Nintendo Switch game console, for example, has been notoriously difficult to find in stores since Christmas of 2019, and Google’s results reflect this reality. Both the presence of the “Top Stories” block and some of those same results in the web listings below, illustrate the focus on where availability can be found and the ongoing saga of production and distribution issues. Results about stock, distribution, and availability are rarely seen on other “buy product X” type queries, but they make sense, serve users, and therefore are prominent for the Switch’s SERPs.

What inputs does Google use to do this?

A wide variety of options are available, and it’s likely Google uses a combination of numerous elements to fight spam. Most likely, Google’s inputs are similar to those of rival search engine, Bing:

- Shifts in query volume – a significant spike in demand often indicates new searchers seeking different results.

- Shifts in publication volume, especially from news sources. When many publishers write about a topic, it can indicate content that’s newly relevant.

- Pogosticking – the degree to which searchers who click on a result do or don’t return to the search result and choose another listing.

- Query refinement – many searchers will use a broad keyword, and then, if unsatisfied by the results presented, a more specific one.

- Growth of related search phrases – when a large number of searchers use a search term or phrase in combination with trending topics, Google might see fit to include those results in with the broader term.

- Searcher satisfaction – Google will sometimes show mini-surveys or ask searchers whether their query was resolved, and this data may be put to use.

One half of what’s “dirty” about this ranking element is ongoing denial of use by some of Google’s employees (though, most marketers already disbelieve a plethora of Google’s public statements). The other half is what engagement signals enable from those with significant audiences.

In Nintendo’s case, the shift in searcher demand is an unintended consequence of meteoric demand and low supply. In Fox News’ case, the shift is an intentionally orchestrated move designed to sow fear and discord (and drive eyeballs from TV to websites and back again in through a monetized treadmill of outrage).

Brands, politicians, media conglomerates, social activists, and sources of influence are slowly waking up to this reality and taking advantage of Google’s searcher-serving, but abuse-able method for manipulating the top rankings. Fox News’s search marketing tactics aren’t about improving the relevance, quality, authority, or value of their web pages, but about driving a new kind of searcher to a query, counting on Google’s preference for engagement, and through it, harnessing the eyeballs, hearts, and minds of many non-Fox-News-driven searchers, too.

When publications and sources of influence have the power to change how people search, they also have the power to change the results. For companies, this can be a powerful way to shift consumer demand from generic searches to branded ones. For social movements, it’s a useful way to educate those whose attention you’ve earned about what your slogans, phrases, beliefs, and goals might be. For news publishers, especially those with politicized audiences, it’s a powerful, but dangerous tool to reinforce bias and steer a conversation.

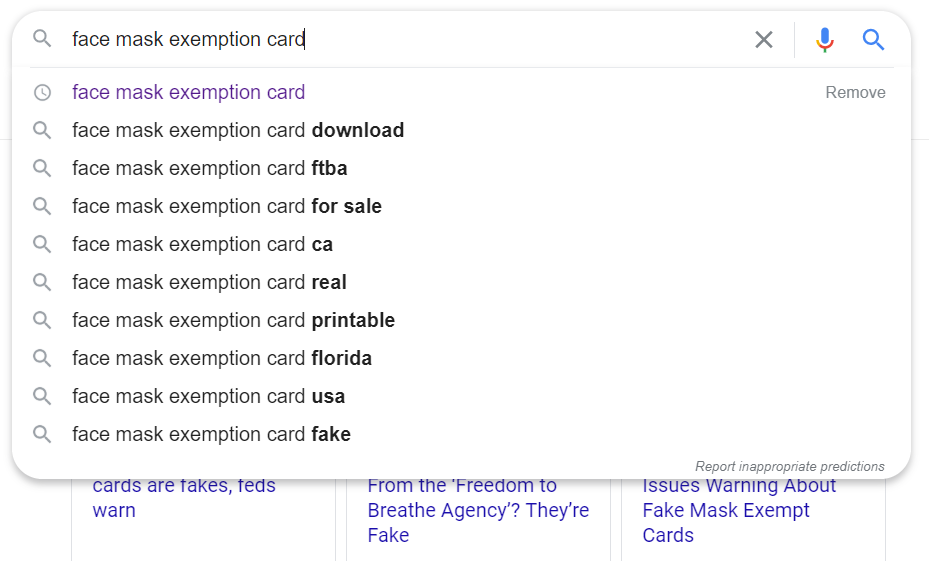

The ability to shift searcher demand doesn’t just change results, but the nudges Google gives us about how to search, too.

Google’s been working hard to tamp down misinformation amidst a continually surging pandemic that the United States is uniquely bad at containing. They’re fighting against not only misinformation, but their own algorithmic preference for engagement.

Pro Tip: do not watch the YouTube videos that rank atop queries like these or your suggested videos will cause your partner great distress

To me, this is a problem without a clear-cut solution. Google’s use of engagement signals brings great benefit. It surfaces the information searchers want more often, higher up, and encourages content creators to better serve their audiences. The dark side is that it sometimes hands weapons of mass misinformation to those with significant audiences and less-than-noble intentions. And like the company’s problems with conspiracies, misinformation, and hate-speech on YouTube, manual review and removal can’t get the job done.

P.S. If you haven’t already, check out this series’ Part 1 on Google-Owned Rankings and Part 2 on Paid Listings.