Yesterday, we explored how Google puts their own products before any others, often regardless of quality. When they do, *even* when those results are superb, it discourages competition. Why bother building something better if Google’s going to send 70, 80, 90%+ of the search traffic to their own property?

Today, we’ll look at how Google uses another kind of dirty ranking secret to extract billions in revenue from those who’ve built impressive brands.

Snake River Farms sells some lovely beef. Over the last 5 years, they’ve managed to build an extraordinary brand online and off. People search specifically for their products far more than for the generic keywords of what they sell (Northwest Beef and American Wagyu).

This brand-building has positive results for the company’s marketing across the board, search marketing in particular benefits. That’s because, when a potential customer queries “Snake River Farms,” the rancher doesn’t have to compete against hundreds or thousands of other websites. They’re nearly guaranteed to be ranking in Google’s top position. After all, the searcher is looking for them!

That, is, unless…

Unless they don’t pay Google to rank in that top, advertising position. In that case, their competitors can come into that top spot and siphon away valuable SERP real estate, brand attention, and search clicks. Even when those competitive ads don’t earn many clicks, they can still dramatically detract from a buyer’s journey by creating doubt and uncertainty.

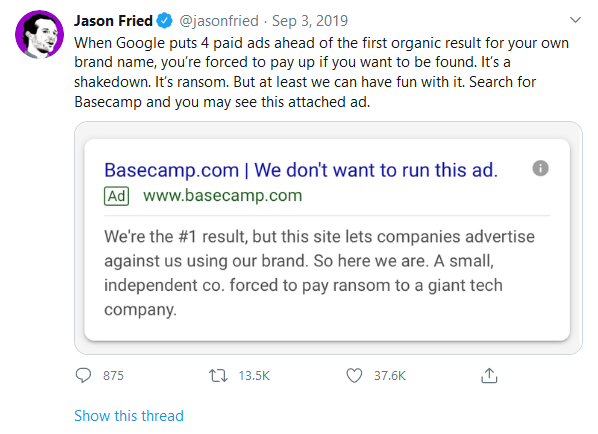

This dirty secret to ranking #1 famously came up late last year when Basecamp founder, Jason Fried, took the search monopoly to task for what he described as an extortion-like practice.

Shopify’s Tobi Lutke had one of my favorite responses:

“Nice, high-intent traffic you got there… It would be a shame if something were to happen to it.“

Google, for their part, has a defense that, on its surface, seems reasonable. They claim that it would, in fact, be anti-competitive to prevent ad bids on trademarked names. Several anti-trust attorneys I spoke to last year confirmed this. Disallowing competition from bidding on trademarked words and phrases could have anti-trust implications.

However…

Google doesn’t *have* to put those ads above the organic results. That’s an intentional choice they make, one with extraordinarily lucrative consequences. The dirty secret of ranking #1 with ads is that, even when those ads aren’t relevant, they still have greater visibility and become a source of potential bias for the searchers who see them. For most of Google’s early history, ads appeared on the sidebar on desktop. The rise of mobile showed Google the power of ads above the organic content, but even today, plenty of search ads appear in sidebars, below, and between the organic results.

The crux of this issue is relevance. Google *knows* the most relevant website for a brand search is that brand’s official website. Disney (as shown above) likely pays a relatively small sum per click for the ad that shows on a query like “Disney+.” But, multiply that small sum by millions of clicks, thousands of branded search queries, and hundreds of thousands of brands and it’s easy to imagine the billions Google earns from this practice.

Take an example like this search for Stripe, the payment processor. Google likely sees extremely low click-through-rate (CTRs) on ads from Stripe’s PPC competitors, Gravy and Chargebee. Many of the PPC specialists I know will privately have data showing that the minimum threshold Google usually has for paid ads is lower for competitive brand buys.

It makes sense—if Google had the standard CTR and quality score requirements, competitive ads for brand searches would have a tough time ever showing up. And without that threat, numerous brands would opt to pull back their paid brand spend (in the ongoing pandemic and economic recession, many already have).

Other arguments for buying branded search include:

- Bolstering your Google Ads Account’s overall quality score

- Getting relatively “cheap” paid clicks

- Increasing “incremental” traffic (most sources point to a 2011 study from Google themselves arguing that 89% of searchers who click those paid ads from a brand would not have clicked the organic results for the same site; a stat that beggars belief)

- Dominating SERP real estate (i.e. controlling more of what a searcher sees on the page)

- Controlling messaging and target URLs more quickly than with organic techniques

Of these, all but one are answerable with a simple refutation:

Google could easily change that by becoming a better, more relevant, more user-serving search engine. If the search monopoly chose to make navigational queries (those where 9X%+ of searchers clearly want to go to the official website of the brand they typed in) more obviously navigational in their results, those first four points would be void.

It’s only the last bullet point, on controlling messaging more quickly and with greater specificity, that still resonates. And even then, Google could give site owners the ability to more thoroughly change messaging and URLs through their Search Console product.

Jason Fried and Tobi Lutke are hard to argue against. The closer one inspects Google’s practices around the use of that top ranking position as a paid ad, even when the searcher’s intent is obviously navigational in nature, the more any logic other than monopoly-driven-taxation falls apart. Google, by centering navigation for an overwhelming majority of web users around their products in search, browser, mobile O/S, and voice input, has built a painful tax into every brand builder’s budget.

If you don’t pay Google’s brand tax, don’t pay enough, or (like the Schick razors search above) don’t pay enough in all the right places, the search giant will introduce results that aren’t what searchers wanted, aren’t nearly relevant to rank in the organic results, but are just tolerably irrelevant enough to help them extract billions in extra income. The secret to ranking #1 in paid ads is dirty indeed.

Tomorrow, in the third and final part of this series, we’ll explore how top rankings in entirely organic, non-Google-controlled operate.

p.s. Missed part one? Check out how Google owns the #1 result themselves, here.