Despite studying content that overachieves for years, it’s only in the past few months that I’ve stumbled into a mental model I’ve called: Hook, Line, and Sinker. My goal here is to broadly encapsulate *why* overachieving content pieces hit their mark, and why similar, but underperforming pieces miss.

First: when we talk about “content,” we’re talking about all kinds of content: short-form entertainment videos on TikTok, engaging B2B-focused posts on Twitter or LinkedIn, case studies, research reports, funny comics on Reddit, and everything in between.

Second: Overachieving doesn’t mean “goes insanely viral,” “gets 10,000 retweets,” or “ranks #1 in Google for 100 high volume keywords” or any other singular metric for content success. It merely means that, when compared to pieces of similar quality and format, they dramatically exceed the average.

Third: Content is art, not science. Content success relies on human behavior, not the laws of physics. Accordingly, this model is a subjective framework, not a precise formula.

What does the framework look like?

My hypothesis: content which follows this simple, intuitive pattern generally outperforms content that doesn’t.

As evidence, I’ll submit the Internet’s aggregators of high-engagement content:

- YouTube Trending

- Google News Top Stories

- Techmeme / Mediagazer / Memeorandum

- Reddit r/All

- Hacker News

- SparkToro Trending

- Most Viewed on TikTok

- Twitter’s Trending Links

Study the pieces that consistently perform well in places like these and you’ll find this model applies with shocking frequency. Moreover, when the model doesn’t apply (i.e. a piece’s headline creates no curiosity, fails to deliver on the expectation created, and lacks an emotion-generating, memorable close) the content doesn’t appear.

The Hook: Grab Attention, Make a Promise

In The Hook, titles, headlines, featured images displayed as previews on social media, and the first few bits of consumable content in a piece are there not to deliver information, but to make a promise of what’s to come.

Above are three examples of The Hook in action.

- Serious Eats’ Favorite Recipes of 2021 makes a compelling promise, especially for those who love the methodical, test-kitchen site’s approach to cooking. The photo of pasta further teases this promise, saying “don’t you want to know what this is? And how to make it?”

- Vox’s Welcome to Covid-19’s “junior year” headline is less promise-filled, but uses a growing-in-popularity social media meme sure to grab attention, then deploys the subheader (especially “What are Americans to do?”) to make the promise of what’s to come.

- BBC’s Alexa tells 10-year-old girl to touch live plug with penny seems like the kind of headline that tells the whole story, but in fact, it’s such a unique, surprising, and clearly-delivered bit of information that it demands a click to learn more. This headline was so engaging, it sat near the top of Google News for several hours until an even-more engaging headline on the same story took over: Amazon Alexa slammed for giving lethal challenge to 10-year-old girl (from Bleeping Computer)

None of these pieces are massively viral hits, but all of them significantly outperformed hundreds of similar competitors in their topic spaces. And if we analyze those big, viral hits, we can see the same pattern at work, especially the curiosity-triggering headline/image/first-few-seconds.

The Hook can sometimes be mistaken for “clickbait,” and if the subsequent content doesn’t deliver on the promise made, or delivers in a subpar fashion, that’s a reasonable charge to level. But, while clickbait makes an unfulfilled-promise, Hook, Line, Sinker does the opposite.

The Line: Deliver on the Promise, Trigger Emotions

The Line isn’t meant to be literal. It should almost always be more than a single line (unless we’re talking TikTok or Twitter). The Line’s purpose is to satisfy the curiosity created by your headline/preview. You’re producing the meat—a story, an explanation, a dataset, a visual series—that quenches the visitor’s thirst for knowledge, entertainment, distraction, or resolution.

The key is to do this in a way that triggers an emotional response. Certain emotions are more correlated with sharing than others, e.g. surprise, fear, hatred, and anger are well-known to incite an engagement response (one of the reasons social media algorithms that prioritize engagement result in so many negative side effects). But, plenty of high-performing pieces leverage other emotions: wonder, joy, satisfaction, gratitude, empowerment, comfort, shame, pride.

In recent years, especially on social media, the emotional resonance of “feeling seen,” has been an especially powerful trigger crafted by stories of shared identity, struggle, injustice, and success. Similarly, the power of controversy, even on entirely trivial subjects (e.g. a human man on planet Earth believes running pizza under cold water is an acceptable way to cool it down; this was 2021’s most upvoted unpopular opinion).

A superb example of delivering, nay overdelivering, on a headline’s promise came from Grub Street’s in-depth journalism on the great bucatini shortage of 2020.

Above, you can see all the elements of an excellent Hook. A great headline and subheader, a perfectly-matched hero image, and a killer intro paragraph dripping with sarcasm, humor, characters, and a story to come.

Friends, that story is even more incredible that you might imagine. Read for yourself:

Bizarre. Incredible. Detailed. Ludicrously well-researched. An almost unbelievable quantity of rabbit-hole-revealing phone calls, emails, rumors, and conspiracies.

It’s not merely the quality of the writing, delightful though it is. The Line of Grubstreet’s piece is the strength of both substance and style reinforcing one another. The comments on Reddit (where the piece did quite well) kindly call out this impressive journalistic duality.

Obviously, the medium of longform, journalistic dive into pasta shortages will reward attributes unique from, say, a 30-second explainer video on LinkedIn or a webinar about desalination plants. But The Line, the substantive bulk of the content, delivering on a promise, in an emotionally resonant way, remains critical to any content piece’s success.

The Sinker: Make the Message Last, Inspire Sharing

Many content pieces that have success—top Google rankings, lots of social shares, high visitor engagement, etc—can reach that success with just the first two of the elements described here: The Hook, and The Line. However… almost every content piece, video, audio, text, graphical, interactive, or multimedia on every platform that went truly “viral,” nailed this final element: The Sinker.

The Sinker is that singular, powerful, lasting memory that makes a piece stick with you. It’s the “I’ll have what she’s having” (from When Harry Met Sally), the “I can see Russia from my house” (Tina Fey as Sarah Palin… or wait, maybe Palin actually said it?), the light saber sound from Star Wars (you can hear the vwoosh sound in your head right now), the first bite of al dente pasta after a childhood of soggy noodles.

Here’s the real secret: there is no one Sinker.

The Sinker is different for different content consumers. The one memorable line, incredible takeaway, photo you’ll never forget, the way the piece made you feel… For someone else, that wasn’t The Sinker, it was ______________. All those conversations you’ve had about a book you read, a movie you watched, a podcast you listened to when you said “I can’t get over X,” and they replied, “really? For me it was Y,” should reinforce this secret truth.

The Sinker might exist in multiple places in different ways. It could be a photo in the midst of a text-heavy essay, or a one-liner delivered near the end of a short video. It could be a chart that cleanly summarizes paragraphs of data, or a gut-punching paragraph that explains why the boring-looking line chart is actually interesting.

Your job as creator isn’t to deliver only one of these potential hits, but to strike those chords again and again throughout your content, then remind the reader/viewer/listener at the end.

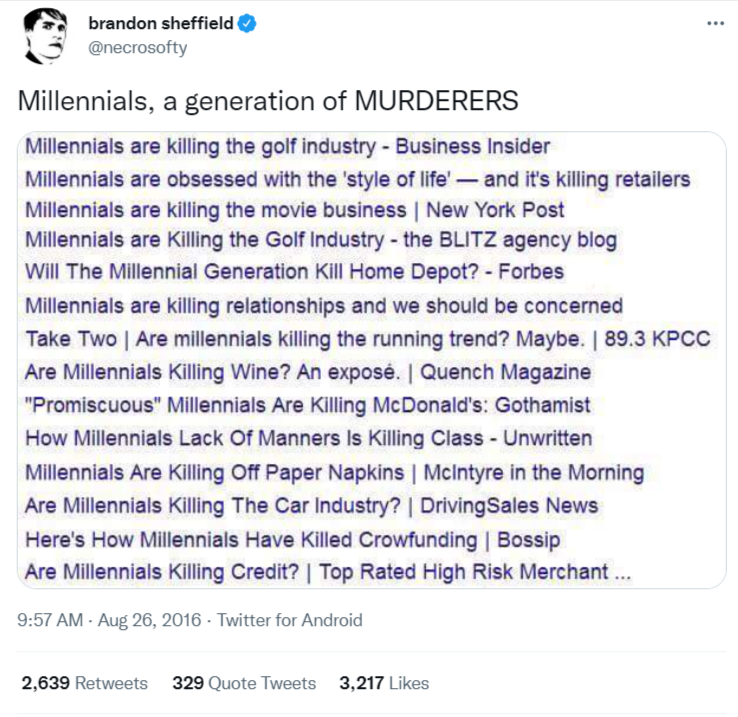

Here’s an example: Millenials Aren’t Killing Industries. We’re Just Broke And Your Business Sucks. It’s an older piece (from 2017) that “strikes back” at the idea that people born between the arbitrary years of 1981-1996 are responsible for the downfall of certain goods and services.

The Sinker for some (as seen in social sharing and comments) was the statistics of how much less this group will make than their older counterparts at similar life stages. For others, it was the embedded chart showing clear lines of exactly how much less at which ages. Still others resonated with the punchy critiques that helped them feel seen, e.g. “We aren’t malicious. We aren’t unpatriotic. We aren’t even that broke. What we are is smart enough to know the difference between a good business and a bad one.”

The embedded tweet from Brandon Sheffield struck a chord, too:

At the conclusion of the piece, the writer reminds readers of the hits, then strikes a final, emotional, memorable blow by proudly owning the power of this industry-killing ability.

I must admit though, after being called lazy, whiny, participation trophy-loving snowflakes by past generations for so many years, it’s nice knowing that we’re now verifiable killing machines feared by titans of industry around the world.

Conor Cawley for Tech.CO

The Sinker needs to make the piece stay with the consumer, make it something they think about later, consider sharing, associate with other ideas, want to include in their email newsletter—you get the idea.

My favorite example? The New York Times’ How Y’all, Youse, and You Guys Talk. Published in 2013, even 5 years later, according to NYT sources, it was the page that had received the most traffic in the website’s history. Sure, it’s got a great Hook and Line, but the real key is The Sinker — everything about the content focus, design, and especially, the end, inspires memorability and sharing. Take the quiz and see if you can resist sending it to someone whose linguistic origins have you curious.

Do me a favor, next time you’re writing a piece, filming a video, recording a podcast, sending a newsletter… try the Hook, Line, Sinker model. If you don’t have one, and can’t come up with one, consider following in my colleague, Amanda’s footsteps (from her newsletter, The Menu):

Even better than attempting to retrofit a struggling piece is applying that energy to a more-worthy, more-success-likely content candidate. It serves no one, least of all yourself, to create content devoid of purpose, destined to fail.