I don’t believe there is any greater, more public example of capitalist-driven marketing on display than the American presidential elections. It is, unquestionably:

- A globally-followed event

- A marketing-driven (rather than product-driven) outcome

- 10X+ larger in spend than any other marketing campaign on Earth

Ad spend figures from Quartz, Nielsen, & OpenSecrets

This pinnacle of influence-driven action is much more than that, obviously. It has potentially disastrous or uplifting consequences for hundreds of millions of Americans and (for most of the past century, though perhaps less so in the future) billions of people around the world.

For that reason, every night this week, here on the SparkToro blog, I’ll be posting about a few of the marketing lessons we can learn from this year’s record-breaking election. The process epitomizes so many valuable marketing, market research, and audience analysis lessons, I felt compelled to dig deep on 2020’s outcome, data, and enduring complexities—so deep it’s too much for a single post.

Map of Voting Pattern Shifts | Source: WaPo

I hope you find these takeaways worthy of consideration, even if you disagree (and if you do, I’d love to have a kind, respectful discussion in the comments). But, before we begin this analysis, I should first make you aware of my perspective. I have three core beliefs that bias me toward progressive points of view:

- Willingness to sacrifice the welfare of those less fortunate to prop up one’s own wealth is a selfish, immoral stance.

- Systems and incentives govern behavior. Personal responsibility exists, but is ineffective in changing behaviors at scale.

- Any political party that discourages turnout, erects barriers to voting, or fails to tear down structures that prevent equality of voter influence deserves to fail (e.g. a Wyoming voter should not have 3.6X a California voter’s influence on federal elections), no matter their other policies. The Democratic Party was guilty of this practice in decades past and deserved repudiation, just as the Republican Party is now.

Thus, like the majority of Americans in seven of the last eight presidential elections, I supported Democratic (and some independent, progressive) candidates in 2020.

Those viewpoints expressed, my goal is to make this week’s posts a non-partisan analysis. Undoubtedly, my biases will seep into the data I present and the conclusions that data leads me toward, but having been transparent about it, you, dear reader, can draw your own conclusions.

#1: Identity and Behavior Are Inextricably Linked

Why do we choose to take the actions we do? Why do we support the beliefs we hold dear? Are we individuals with free will and independent thought? Or do our beliefs and behavior derive not from consistent principles but from what our cultural identity biases us toward.

At an individual level, I think it’s the former. A person can make up their own mind, and plenty of people take up positions and engage in behaviors that don’t match up with their social identities, the geography they come from, the families they’re born into, etc. But, any time scale is involved, behavior patterns emerge. Those patterns are nothing like the individual-level. They’re driven, especially in the United States, by group identity.

My favorite example are the responses to one of sports broadcaster ESPN’s 2015 reader poll. The NFL Patriots (an American football team) removed some of the air from footballs in order to gain a physics-based advantage in their matches. You can see who responded, and how, below:

Via SBNation’s Coverage of ESPN’s SportsNation Polls

What’s going on there? Simple. The overwhelming majority of respondents asked about the New England Football Team’s actions found them to be dishonest. But, in one particular geography, respondents answered the opposite way.

Are New Englanders more gullible than other Americans? Less able to identify falsehoods? Easier targets for obvious grifters?

Unlikely.

They’re merely cultural members of the identity group that emotionally benefits by believing their team’s coach and quarterback. Support for their team overruns their good judgement, incentivizing them to respond differently to the same evidence that convinced people from every other region, the NFL’s governing officials, and an impressive set of scientists that the Patriots did, probably, cheat.

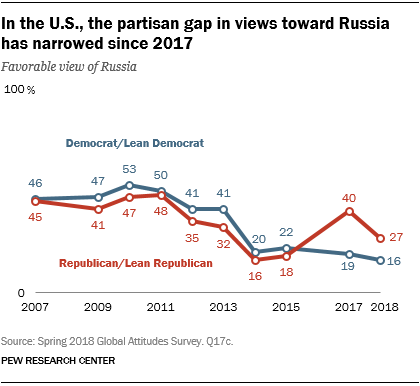

A similar thing happens when we look at how partisans in the United States view the Russian government over time:

For almost all of the 20th Century, and the first 16 years of the 21st, Republican-leaning Americans had less favorable views of Russia than their Democratic-leaning compatriots. But, suddenly, at the end of 2016, positive perception of Russia among Republicans skyrockets.

Much like New England-based support for their team’s obvious lies, these voters’ changed their beliefs, almost overnight, because positive sentiment toward Russia (which worked to assist Donald Trump in the 2016 election) tied to their identities. Believing good things about Russia’s intent became crucial to explaining support for their preferred candidate. Rather than shifting identities away from their political party, they rationalized why Russia’s promotion of Trump was, actually, a good thing.

Had Russia’s influence operation favored the Democratic candidate, the chart would, unquestionably, trend the opposite way (for both groups). Much as I’d like to believe that my own behavior in that scenario would be rational, I’m sure that I, like many other Clinton-supporters in 2016, would have convinced myself that Russia wasn’t all that bad for interfering on behalf of my candidate.

We see this identity → behavior effect repeated in 2020’s politics, when Democratic fears that the election would not be “free and fair” shifted to strong belief that the process had been (once their candidate was confirmed as the winner). Similarly, Republicans’ beliefs (slightly above that of their Democratic peers prior to the election), dropped significantly once their candidate lost.

Via Politico/Morning Consult Survey

Marketing Takeaway: Identity is an immensely powerful force for influencing behavior and shaping belief. Your potential customers have cultural, geographic, professional, and likely numerous other associations deeply tied to their identities. These identities lead to pre-existing beliefs that your marketing can either take advantage of or be hamstrung by.

Consider the relentless defenders of Apple products, Tesla stock, Bitcoin (or other cryptocurrencies). These companies have fastened their brands to their customers’ identities and earned near-political levels of support. But, this is a slippery slope, as cultural identities and branding can have adverse as well as positive effects (i.e. you often make strong bonds with your customers, but attract unusually strong detractors as well). Make a conscious decision about whether identity-based marketing is for you, because as politics teaches us, dipping your toe in the water isn’t an option. It’s (usually) all or nothing.

#2: A Common Enemy Is An Immensely Powerful Marketing Force

Presidential candidate Donald Trump was historically unpopular among his own party and independents when he became the Republican nominee in 2016. Videos of his now-supporters calling him a conman, liar, abuser, and worse regularly achieve Internet virality. But, despite that unpopularity, a slew of reprehensible actions, and an unfavorable environment for a challenger (given economic growth under the opposing party’s predecessor), Trump narrowly won the anachronistic electoral college and through it, the presidency. How?

Countless explanations abound, but none is more widely credited than the decades-long, exceptionally successful negative branding of his opponent, Hillary Clinton.

Via Pew Research

2016’s election wasn’t a battle for “whom do I like more?” but, rather “whom do I detest less?“

This year’s narrative isn’t as bi-directionally true, as President-elect Biden was not nearly as maligned or hated as Ms. Clinton, but data does show that over the course of his presidency, Trump was a historically unpopular President (though his approval ratings among partisans remained stable throughout). This disapproval became a lightning rod for his opposition’s ire, fundraising, and turnout.

Via CNBC / Center for Responsive Politics

Re-elections of sitting Presidents are almost exclusively referendums on the White House occupant, and 2020 was no different. As many pollsters noted, Trump’s “priors” were quite favorable, and in the past 100 years, only 4 sitting presidents lost to a challenger. But, in 2020, the power of a “Common Enemy” contributed strongly to this statistically-unlikely outcome.

Marketing Takeaway: Almost every brand, product, and company has the opportunity to position themselves in opposition to something or someone else. Unlike politics, it doesn’t need to be particularly heated or controversial to be powerful. Gatorade made “thirst” and later, “losing” into enemies (hardly controversial opponents). Facebook’s growth was not-so-subtly driven by an opposition to the lonely, disconnectedness of modernity (ironic though that may now seem). SparkToro itself has relentlessly focused on expanding marketing “beyond the Facebook and Google duopoly,” and benefited from those common enemies.

No matter what you do, it’s worth evaluating if there’s a common enemy (even if it’s just an “old way of doing things”) that can help you stand out from the crowd to create passionate customers and supporters.

Stay tuned for Part II: Positioning and Segmentation, appearing on this blog tomorrow. And, as a reminder, while I’d LOVE to hear your thoughts and have a great discussion in the comments, let’s try to keep it truly kind and respectful. Due to the risky nature of political discussions, I’ll quickly delete any comments that don’t go that route 🙂