If you were to perceive the world based on a skim of my Threads feed this morning, then you would be convinced that absolutely everyone is engrossed with the Beckham family drama, the only other pressing matter at hand is whether to recline your airplane seat, and the cost of $0.79 for a garlic bulb is exorbitant to the point that the average American cannot afford it. (I know, none of that makes sense.) Now, personally, I have no idea how many people are even in the Beckham family, I almost never think about airplane seats even while I’m mid-flight, and not to brag, but I literally have half a bulb of garlic on my kitchen counter right now.

None of that is real. I mean… it’s real, like some people agree with or disagree with those things. But they don’t matter, and I’m willing to bet real money that you don’t care about them either. Because all those things? They’re not facts. They’re just vibes. But they do represent a very real shift. Last week, my colleague Rand Fishkin (you might know him) noted that the world we now live in is governed more by algorithmic feeds populated by strangers rather than by friends, family, or journalism. Yes, these stranger-generated vibes do not run the world, but they sure do shape the world’s collective perception.

We marketers love to argue in absolutes. It’s either, “Data always wins!” or “Nobody cares about your boring numbers!” After all, nuanced discussion is messy and it’s hard to hold two truths in your head at the same time. Brain lazy, need answer, want cool story, dopamine dopamine chomp chomp chomp. Perhaps the more optimistic reason for that is that people have always been easier to persuade with stories than with statistics. That’s… kind of the whole basis of religion, isn’t it? To believe based on faith, not empirical proof.

Daniel Kahneman’s work on fast vs. slow thinking explains this cleanly: we form impressions quickly and emotionally, then rationalize them later with evidence if it’s available. The affect heuristic shows the same thing: feelings (or vibes?) act as shortcuts during decision-making, especially under uncertainty. Applied to marketing, this tells us that the responsible thing to do is to tell that effective, emotional story, backing it up with real proof.

In 2026, that balancing act matters more than ever. Good marketing brings forth the facts, carried by vibes. The facts, data, evidence, and hard numbers earn you credibility. The vibes, feelings, and emotions you wrap them in earn you attention. To persuade audiences, you need to know how to deploy each.

Facts alone don’t automatically change minds. (Ha! If only it were that simple. Then we wouldn’t be here *waves hands vaguely and wildly at everything*.) People selectively accept information that aligns with what they already want to believe. Even worse, correcting misinformation can backfire when it threatens someone’s identity. So unfortunately, we can’t just dump a bunch of charts into a post and expect them to make the point for us. We have to know what types of facts to use and when.

And here’s where my career in health tech comes in really, really handy. Looking back on my time at health (er, healthy-ish) snack company NatureBox and fitness tracker company Fitbit, I quickly got used to having to source every single claim with research. At Fitbit, I even got to work with a wonderful legal team who helped me defend ideas more rigorously. Here’s a good starting point for determining what types of research to cite.

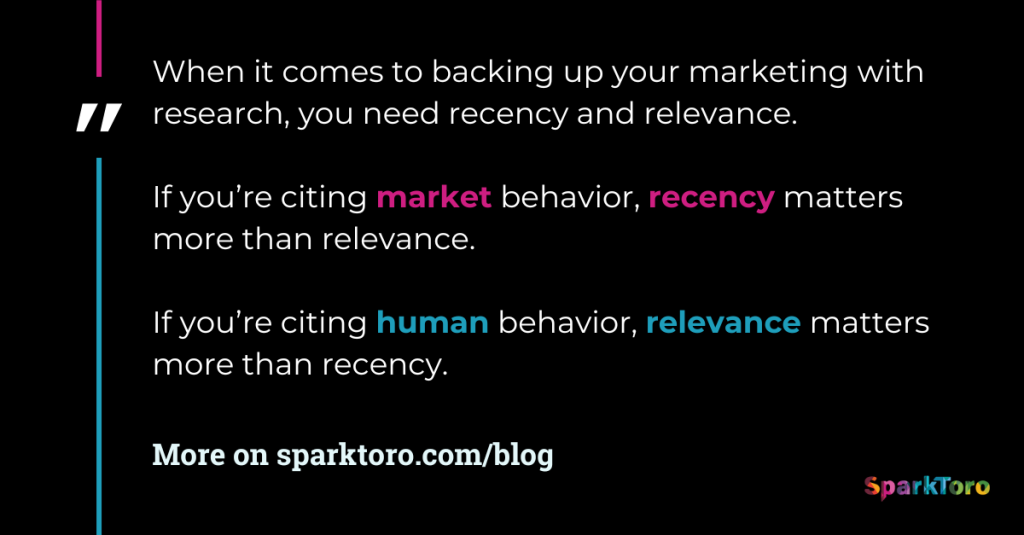

Spoiler alert: recency vs. relevance

I started this blog post thinking about surveys and polls vs. academic studies. But I realized we can start much simpler than that with this rule:

If you’re citing market behavior, recency matters more than relevance.

If you’re citing human behavior, relevance matters more than recency.

Market behavior changes quickly. The human condition, less so. Let’s say you’re trying to get a pulse on an entire industry. Look for recent research. In fact, if you’re curious about the outlook on digital agencies this year, Paddy Moogan’s and Rand Fishkin’s 2025 State of the Agency survey is a great place to start. (Shameless plug, but hey, you’re on my blog, this is what you get.) But if you want to know what drives people to their purchase decisions, you’re actually curious about psychology. In this case, it’s relevance that matters. Maybe you want to read up on the mere-exposure effect, where people tend to develop preferences for things that they’re exposed to for longer. And while you’re there, look up the IKEA effect and recency bias too.

Not all facts are created equal

Once you internalize recency vs. relevance, you can start thinking about the type of facts you need to source. Not all data is created equal, but some of them do belong in multiple categories. An observational study and a sentiment survey are two very different things, used for very different purposes. A classic peer-reviewed study could be cited across multiple different marketing use cases. And pithily referring to a recent news headline may be factual, but it doesn’t carry the same weight as a longitudinal dataset.

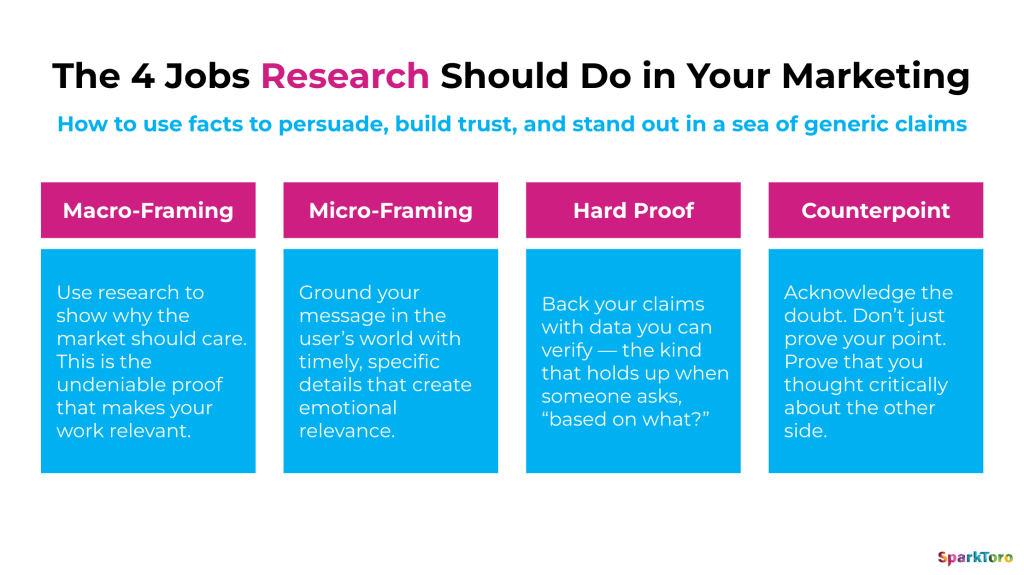

Here are the four most common uses for facts/research/concrete details in marketing:

Macro-Framing (a.k.a. “Here’s why the market should care”):

Give the context for why you exist and why you care — the massive problem you’re solving and how you’re uniquely positioned to fix it. Think of it as speaking to the entire market; this is where credibility matters most.

Examples of fact types to use include but are not limited to: industry outlooks; platform usage trends; economic indicators.

Micro-Framing (a.k.a. “Here’s why the user should care”):

This is the challenge that plagues every content marketer. It’s backing up why you’re saying whatever it is you’re saying. Use concrete details to establish context. They don’t prove your whole thesis, but they orient the reader in the current reality. You could even use micro-framing to first make sure readers feel seen — so that they become open to your argument. Your concrete detail could be, “Rand Fishkin recently wrote about five trends he foresees in marketing in 2026… here’s my take on one of those trends.” Or your concrete detail could be leading with the results of an industry survey, like Sprout Social’s annual State of Social Media survey.

My two cents is to match it by size or impact. If you’re making a claim as small as, “You want your audience to care,” you don’t need a citation for that. Anyone who makes anything ever wants the person it’s for to care about it. But if your claim is a little spicier like, “Email open rates are higher than ever,” then you need to back that up. And by the way, since that’s a take on how something has evolved over time, then it’s probably a good idea to look at longitudinal data, and you better get some stats from the recent several months because of your use of the words “than ever.”

And here’s where you might need to get even more specific. Because when I say “Here’s why the user should care,” I’m also asking you who that user is. That user might be your target customer — or it might be a journalist whose job it is to understand the market need where it meets the individual. A user cares about how a product demonstrably improves their life. A journalist cares about why that matters at scale.

Examples: peer-reviewed studies; a statement that has gained traction in your niche; survey results; poll findings; a screenshot of an analytics page; recent news.

Hard proof (a.k.a. “This is how this thing is effective.”):

These are your guardrails. They prevent you from making claims that are demonstrably false and protect you when someone inevitably asks, “Based on what?” You’ll want these to prove how/why your category or industry is important. In the case of Fitbit, these were proof points to show that exercise is healthy, cardiovascular health is important, and heart rate is a measure of health.

If you’re thinking about this on the company or product level, then think about what proves your impact. Use verifiable data. This could be pulling usage metrics from your database, or quoting a happy customer who’s willing to go on the record with their statement. The through line is that these are facts that you own — which, if you’re wise, you’ll realize means will be more subject to skepticism. So check and double check your work. (Using the Fitbit example again, this included case studies, in-app usage, number of steps walked in the community.)

Examples: benchmarks; longitudinal datasets; peer-reviewed studies; your CRM data; testaments from actual customers; your social media metrics… well, if you’re speaking within the context of your own social media.

Counterpoint (a.k.a. “Yeah, but you’re wrong…”)

Especially when you’re operating in skeptical markets or highly competitive spaces, it’s useful to include facts that acknowledge the opposition. These are the acknowledgements to the naysayers. It’s where you would add to your claim, “Yeah, it is true that Apple’s Mail Privacy Protection and security filters have artificially inflated opens, but email opens were trending up before those security measures became more pervasive.” Then maybe you’d add a new claim: “What you should instead track more closely are response rates and conversion rates. This week at SparkToro, the email campaign of our new Describe Your Audience feature got several really nice replies. Not all of our campaigns lead responses, so this felt like a sign we’re onto something.”

And sometimes, especially in the case of when you’re discussing ideas or experiments, it’s not about having a perfectly bullet-proof claim. It’s your ability to acknowledge the nuance and accept the correction for edge cases that can make a world of a difference.

Examples: news; additional studies; screenshots.

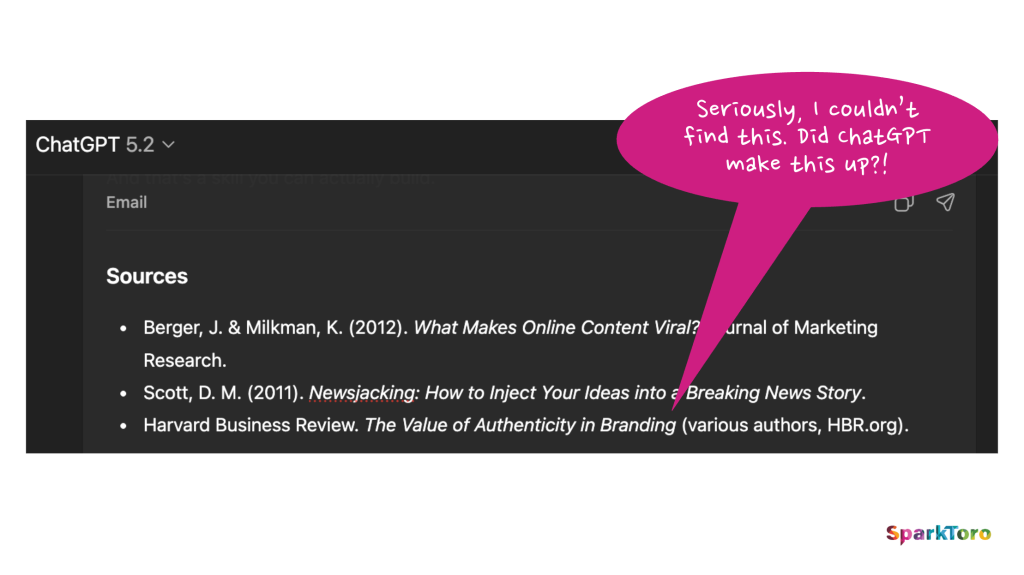

Applying the right research is where writing like a smart human really shows. LLM-style writing stacks often-true-but-sometimes-hallucinated facts to simulate authority. Human writing chooses facts intentionally, with each one earning its place in the argument.

What “writing like a smart human” actually looks like

Writing in 2026 is striking the right balance of vibes and facts. Vibes determine what feels plausible, and what gets clicked and shared. Facts decide what holds up. They’re what you reach for when an idea leaves the feed and enters the real world, when it’s scrutinized, cited, debated, or used to justify a decision. This is why content that feels right spreads faster. But it’s also why so much of it collapses the moment someone asks, “Okay cool, but based on what?”

In a time when everything seems real — and therefore risks meaning nothing — discernment is the differentiator. Not doubling down and just being louder. Not a smattering of citations. Better judgment.

Make a claim. Support it with recent or relevant facts. Wrap it all in a story worth paying attention to.

That’s defensible marketing.