Welcome to the final episode in our five part exploration of the 2020 US election from a marketing lens. If you haven’t already, make sure to check out the rest of series

- Part I: Identity & Common Enemies

- Part II: Positioning & Segmentation

- Part III: Polling Problems & Growing Fans vs. Persuading Converts

- Part IV: Narratives & Information Distribution

- Part V: Brand Familiarity & The Weakness of Product (you are here)

These final two takeaways will help us understand a little more of why Joe Biden and Donald Trump had such historic success driving their respective supporters to vote, and then explore an uncomfortable truth: that marketing may be much more powerful than product.

Quick reminders:

- We’ve focused on the 2020 elections each night this week, because its size and impact are so relevant to how we do marketing, market research, and customer research.

- These posts attempt to be non-partisan, but your author (me!) is politically progressive (and I want to be transparent about my bias).

- I’d love to read your comments + feedback, even if you strongly disagree! But, please, keep ’em respectful and kind, or they’ll be removed.

Let’s finish our analysis…

#9: Brand Familiarity, History, and Trust Carries Tremendous Weight

Back in 2016, when Donald Trump entered the Republican primary field, numerous political observers and professional analysts expressed pointed skepticism about his odds of winning the Republican nomination.

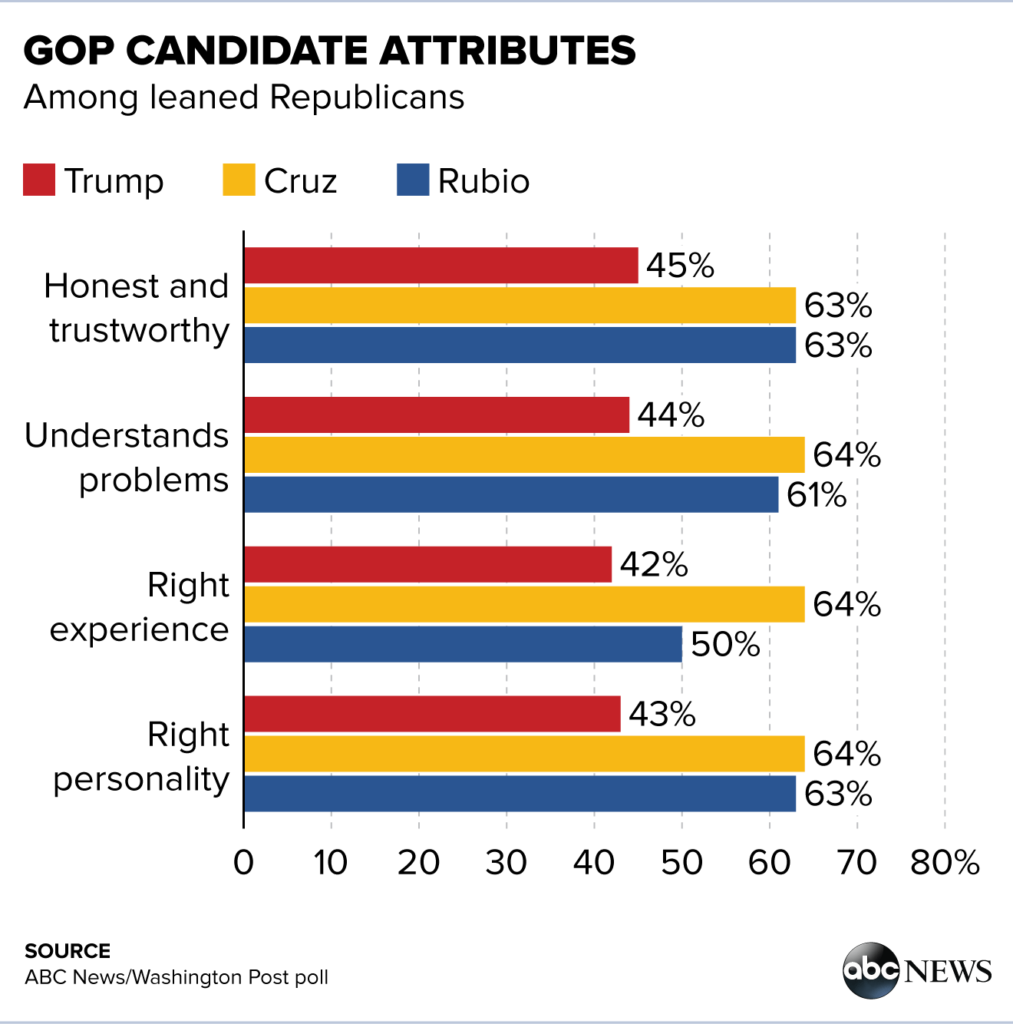

His racist statements, history of supporting/befriending Democrats, multiple failed marriages and businesses, detestable treatment of women (including numerous credible rape and harassment allegations), refusal to pay employees and contractors, and lifelong violations of religious values conservatives claimed to hold dear led to poll after poll showing he couldn’t win. Here’s an example from ABC News, showing Trump badly behind rivals Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio on every issue.

Via ABC News 2016

For anyone who followed the 2016 primary closely, the next few months proved challenging to interpret or understand. Republican politicians, media personalities, and voters continued, right up until the convention, to condemn and reject Trump’s increasingly plausible candidacy. In hindsight, many Americans might point to Trump’s support from conservative media outlets, but that’s a myth, too. In fact, channels like Fox News were vehemently critical of Trump right up until his nomination.

Hindsight in 2020 can, I believe, tell us not just a lot about why Trump won the Republican primary, but also helps explain why he was so successful in the this past election (garnering 10 million more votes than he did in his 2016 popular vote loss / electoral college win). Not only that, it’s an exceptional lesson for marketers in the power of brand repetition.

Minutes of coverage for GOP Primary Candidates via MRC

Donald Trump uncovered two powerful, exploitable hacks in American Media:

- If you continually do shocking, unbelievable things (even if those things are negative or scandalous), the media believes they must cover them. Using this hack, you can dominate media attention, and earn immense brand recognition.

- Because of American media’s prevailing paradigm to represent “both sides equally,” a politician can consistently make spurious, even provably-false claims without being challenged by journalists who’ve been trained to “let the candidates/politicians do the talking.”

These insights, whether you attribute them to strategic genius or accidental discovery, led Trump to literal billions in organic media value.

Media Value of Coverage for the 2016 Candidates via The Washington Post

Trump’s novelty, though disturbing, earned him 10X the coverage of his Republican primary peers, and nearly 2X that of his general election opponent, Hillary Clinton.

Over the next four years, President Trump doubled-down on this strategy. His statements and actions in office were even more shocking than his rhetoric on the campaign trail, and an old hack: the responsibility the press feels to cover anything the US President says (simply because they are the President), became an increasingly powerful weapon in Trump’s branding arsenal.

The marketing lesson here is a simple one: brand repetition is ludicrously powerful. Hear a song over and over, and even if you hate it, your brain will subconsciously hum it. Hear a brand name over and over and you’ll assume the company behind it must be a big, important, and probably trustworthy one. See a person’s name again and again, and even if your conscious mind knows they’re only “famous” in the world you follow, you begin to associate characteristics of importance, value, wealth, gravitas to them.

Most surprising about Trump’s use of these brand repetition hacks was how little the tone and sentiment of coverage mattered.

The 2016 polls narrowed at the very end of the race (after the “but, her emails!” pseudo-scandal), but for most of the election year, Hillary Clinton’s favorability ratings were dramatically higher than Trump’s. Why didn’t it matter in the end?

My suspicion is that human beings, especially when voting, aren’t quite as sophisticated and nuanced as we make them out to be. The superb and widely-shared essay, The Real Divide in America is Between Political Junkies and Everyone Else, opened with this data:

And then closed on this insight:

If the majority of voters don’t follow or care about politics, and are only slightly aware of the candidates’ viewpoints, actions, and comments, then perhaps what’s really happening in elections is the same thing that’s happening in the grocery store.

Scene From a Grocery Store

Consumer: “I need some Ziploc bags.”

Marketer for Alt-Brand: “Here’s fifty excellent reasons why you should choose Alt-Brand resealable plastic bags, instead!”

Consumer: “Uhh… Yeah, I think they’re on this aisle.”

Marketer: “Before you grab your usual Ziplocs, consider that Alt-Brand bags are environmentally friendly, unlike Ziploc, and you literally filled out a survey on your way into the store saying environmental-friendliness was the most important thing to you when considering which products to buy.

Consumer: “Did someone say Ziploc? Yeah, I definitely heard Ziploc a couple times. Glad I got ’em on my list.”

Marketer: “Are you kidding me right now? Oh my god, you’re literally reaching way back on the shelf to get the Ziplocs while pushing our product out of the way? What is happening?!”

Consumer: “OK, Ziplocs acquired, what’s next? Oh yeah… Pop Tarts.”

Marketer: “You hate Pop Tarts! You just complained yesterday about how they taste like cardboard and are killing your diet and… you know what… whatever.”

Consumer: “Pop Tarts, Pop Tarts, gonna get some Pop Tarts.”

Ziplocs. Pop Tarts. Snickers. Google. Facebook. Apple. Amazon.

The problem is that we marketers are so smart, we’re dumb. We’ve lost empathy with and understanding of how default behaviors, driven by lizard-brain triggers like familiarity, recognition, repetition, and association overpower everything else.

I’ll admit, when I see a brand spending hundreds of millions on a terrible Super Bowl commercial or an influencer with an overhyped celebrity, I cringe. But, I’m the naive one. Those brand marketers don’t need my approval or my business, they don’t even need positive sentiment or organic sharing or for anyone to change their mind. All they need is that little voice in millions of consumers heads repeating their name.

Trump raped a 13 year old girl. Trump insults American prisoners of war. Trump barged into the Miss Teen USA dressing room. Trump spent 1/3rd of his Presidency golfing at his own properties, funded by taxpayers. Trump funneled millions in charitable donations to his own businesses and is under indictment for it.

Guess what, friends? What many Americans hear when they see those stories is simply: Trump. Trump. Trump. Trump. Trump.

If you’re reading this blog, you probably pay attention to politics. You’re in the 15-20% who follow things closely enough to have knowledge of those scandals (and hundreds more). You might even buy the eco-friendly brand of resealable bags from the grocery store.

But for hundreds of millions of Americans, all of that scandal and coverage is just “Ziploc, Ziploc, Ziploc.”

That leads us to our final takeaway…

#10: Marketing is Far More Powerful Than Product

One of the most insidious myths in the tech startup world also pervades every other sector I’ve seen: from charities to agencies to consumer product goods to politics. It goes something like this:

Via Twitter

The responses are worth seeing, too. VHS > Betamax, Microsoft > Lotus, Fox News > NPR, Facebook > The Open Web, Bing’s results but with Google’s logo on them.

It’s easy to insult, belittle, or mock the intelligence of the “average consumer” or “average business” or “average voter.” But I believe that’s lazy thinking. People, businesses, and voters aren’t dumb. The problem here is scale.

At scale, large groups of people behave in patterns that, like water over a landscape, follow the easiest path. Every marketing lesson in this series reinforces the broader point:

- Our cultural identities bias us to a default choice

- Common enemies short-circuit our logic centers and make us think like warring sides rather than stewards of a shared community

- Entrenched positioning sticks around long after the product has changed

- Demographics are overly simplistic, but make it easy to classify people

- Predictive data fails when audiences are missed

- It’s often easier to make more new customers than to win them from the competition

- Simplistic narratives may be wrong, but they’re easy to remember, and thus quite effective

- Information isn’t evenly distributed, it’s consumed in the communities that serve groups with belief-reinforcing content

- Brand familiarity drives a huge amount of default behavior

Simplicity. Ease of processing. Mental shortcuts. Asking an individual to overcome these blocks is possible. Hoping that hundreds of millions will? That’s a pipe dream.

If you’re in marketing, you’ve almost certainly encountered articles espousing data about how making a website load 1-2 seconds faster can considerably improve conversion rate. When you reflect on the idea that there are millions of people who would have spent $407.29 on a giant, inflatable toy if only that page had loaded a second faster, it seems impossible. Yet the data proves it’s true!

Cognition & The Intrinsic User Experience via UX Magazine

All of these marketing things we do to make a behavior the simple, easy, default choice in the minds of our audiences are just that: a reduction of load time. We’re reducing how long a brain takes to render a decision so the human being it controls can get on with their life.

It’s important to choose the right politician on the ballot. It’s also important to choose the right babysitter for your kids, and the right car for your commute, and the right way to have that tough conversation with your boss, and even the right re-sealable plastic bag… ah heck, let’s just get Ziploc and get out of here, how much could it really matter?

Marketing Takeaway: Decisions sit on a spectrum. At one end, there’s things like where and whether to go to college, whom to date and marry, and where to live. People tend to put a lot of energy into those decisions, because the impact is felt personally, deeply, and for the long term.

Move further along the spectrum to decisions like where to get lunch, which TV show to watch tonight, or whether to post that photo on Instagram and the energy is less. There’s still a personal impact to each, but the impact isn’t particularly big and won’t have much of an effect on them a week from now.

All the way at the far end of this decision spectrum sits voting. Yeah, yeah, it’s technically the most important way you participate in democracy and it influences everything in everyone’s life, but is it really gonna change my day tomorrow more than what I watch on TV tonight or which sandwich I picked out for lunch?

Taken to an extreme, one might imagine I’m saying that “product doesn’t matter at all.” That’s hyperbolic nonsense. Product influences a tremendous amount of marketing, especially if the product’s impact is felt in the short-term, in a visceral way. But, friends, politics (not just for the 85% of people who don’t follow it closely, but for many of us who do) isn’t felt viscerally, strongly, personally, or in the short-term.

No wonder that in elections, marketing has so much more impact than product. If it didn’t, we’d elect people like James Baldwin, Elizabeth Warren, Stacy Abrams, and Nelson Mandela. Come to think it, some people have elected those folks. Maybe there’s hope yet.

Friends, it’s been an honor (and a metric ton of work) putting together this marketing analysis series. I hope you’ve enjoyed it, that you’ve found it valuable, and that in the years ahead, you’ll think back to these lessons and apply them to your own projects and campaigns.

I’d, of course, love to hear your (kind & respectful) comments below. Politics may divide some of us, but my hope is that this analysis can also help us see our common humanity, too.