The startup ecosystem loves to hype the concept of product-market fit. Does your company have it? How far away from it are you? If you have it, how are you scaling? If you don’t have it, why would you ever try to do marketing?

All of these questions assume a binary truth, universally applicable to all companies and the products they make. In this mythology, it’s either: Yes, you have product-market fit. Or, no, you do not have product-market fit.

But that’s not reality. It’s not even a useful mental model. Product development (new or otherwise) isn’t magically done when some universal metric or level of customer resonance is reached. No matter what you’re making, the process is ongoing, iterative, and fluctuating. Great products don’t stand still. And markets definitely don’t.

Twenty different products at ten different companies might all have different levels of market penetration, share, and growth while having exactly the same Net Promoter Score or Customer Loyalty Score or Customer Effort Score or whatever numerical alternative you might name. And each of these products might have incredibly different levels of success against their actual sales, profit, or growth targets. Infuriatingly, the startup world handwaves this by never giving “product-market” fit a distinct, universally-applicable definition.

Instead, it’s a “feeling.”

If you spend time poking around the thought leadership pieces on product-market fit, you’ll see a weird amount of nebulous, metric-less, “gut feel” definitions. A lot of them even make perplexing graphs with axes like “Depth of Customer Engagement” vs. “Vision for your Customer”. They have quadrants to warn you against the dangers of being too “revenue centric.” No, seriously.

Cue eye-rolling at this VC-made graphic describing how customer traction works because they (checks notes) invested in 1,000 companies, of which 22 made them money.

Lenny Rachitsky’s recent newsletter What it feels like when you’ve found product-market fit, reinforced this mythology. Reading through the many impressive answers from a variety of accomplished founders and product-builders, I struggled with how Lenny didn’t reach the obvious conclusion: that there’s no such thing as P/M Fit.

“Whatever that point means to you.” via Lenny’s Newsletter

His post transparently reveals that there is no clear or consistent demarcation for fit vs. non-fit. And I appreciate that he takes to calling it a “feeling,” rather than a scientifically measurable binary.

Fit vs. non-fit is isn’t how product work, and it’s not how people work, either. Consumers and businesses don’t suddenly switch from a mindset of “welp, this product does not fit my needs and so I will not consider it” to “oh hey, this product is a fit and so I/we will now purchase.” These aren’t even two ends of a useful spectrum, they’re just… baloney.

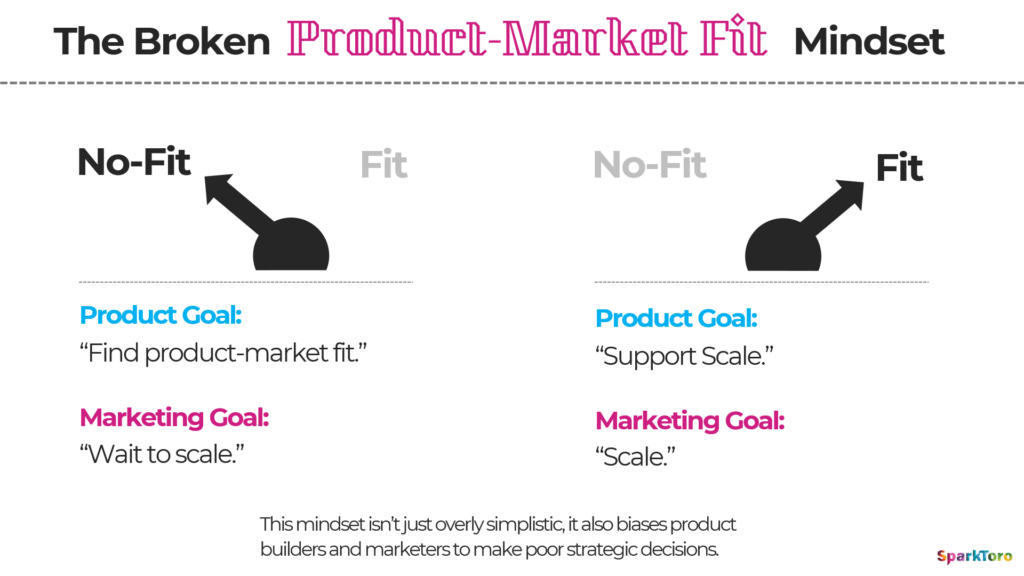

The problem isn’t just this (foolish) assumption that buyer behavior and whatever product-market fit metric or score are binary. It’s that the very concept of fit vs. non-fit biases the people building and selling products to think in ways that harm their potential for success.

4 Dumb Things People Do Because They Believe There’s Such a Thing As “Product-Market Fit”

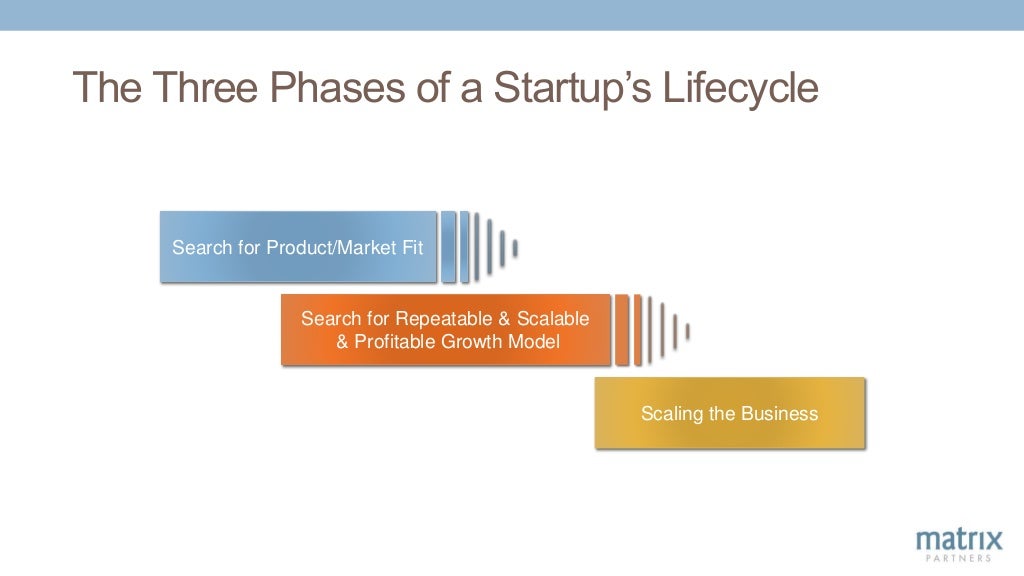

#1: Product builders take different approaches to what and how they build before vs. after the magical moment of product-market fit. We’re told to believe that pre-fit is a time for discovery and learning while post-fit is a time for scale. But product strategy shouldn’t do a 180° based on an arbitrary “feeling” of fit vs. non-fit (even if that arbitrary feeling comes from people earning interest off hundreds of millions of dollars of someone else’s money). Product development is a consistent, iterative process that should be driven by customer input all along the way, even after you “feel” like your product is resonating with the market. I should know, because I seriously f$%#’d up at my previous company believing that we’d found “fit” (at ~$30M in recurring revenue with 20,000+ customers, 60% of whom subscribed to our product for 18+ months), and should, therefore, “scale.” Bad idea, Rand.

A VC-graphic showing how your company’s phase and the activities you should focus on shift based almost exclusively on whether this unmeasurable “product-market fit” has been achieved.

#2: Marketers (and the founders/builders who should probably be doing the early marketing) take a hands-off or brand-only approach to marketing in the months and years before product-market fit is declared. This, in my experience (and from a lot of survey data) is the biggest killer of startups. They declare “we can’t find product-market fit,” when in fact, they didn’t invest enough in finding customers, at profitable rates, to sustain the business. And that happened because they weren’t consistently marketing their customers’ problem and their solution to it, in resonant ways, instead looking for the magical product-market fit moment to “happen organically.”

#3: Investors craft, frankly, silly models of what product-market fit looks like (usually based on small, survivorship-biased samples) and then only seek startups that reach those metrics to invest-in. This creates the belief in many, many companies, even those that shouldn’t be trying to seek investment from venture-style funds, that they should chase a magical “product-market” fit metric instead of a sustainable, profitable business. Worse still, when they hit these metrics and return to the potential investor, they’re still turned down (because “metrics” were just an excuse for whatever real reason the investor said no).

#4: Founders and product builders ignore many of the real inputs that go into gaining market traction, selling their product, or earning users, especially pricing, positioning, and brand. It’s often the case that investments in these tactics—modifying price points, positioning your product’s solution differently or to a different market, and/or earning more brand recognition, likability, and trust—will have huge impacts on growth. But magical belief in a “product-market fit inflection point” shifts all the weight onto the product itself, and limits creative ideas around what might solve the company’s issues.

The real question should be: is there any value in thinking about product-market fit as a true or false statement? Does the startup world glean greater survival rates or make better products or prioritize their team’s time better by thinking about this problem as a binary?

Should we listen to firms like Andreesen Horowitz (1) or startup marketers like Brian Tod (2) or influential investment partners (3) simply because they’ve watched, advised, or invested in lots of companies who’ve failed at this (and a few who haven’t)?

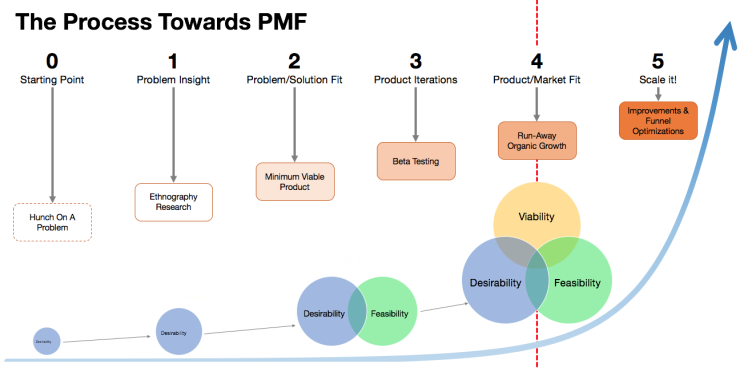

Graphic from Brian’s post about P/M Fit, which (IMO) biases companies to make some really bad decisions about when or how to go about building and marketing.

To me, it’s a clear no. I cannot see a benefit or value-add to product development, gathering of customer feedback, marketing, or any aspect of the company’s strategy or its tactics. The only way fit-vs.-no-fit is helpful is in its simplicity. And by now, I should know better… We should know better than trust simple > complex when it comes to building and marketing things to people.

A Better Model: The Customer Adoption Spectrum

The most obvious ways to improve on the product-market fit mindset are:

- Remove the concept of a binary yes/no

- Apply a range (since any useful metric falls along a spectrum)

- Use segmentation (as product and marketing professionals need these to wisely prioritize work)

With a little visualization, this is an easy problem to solve.

Now we’ve not only got a better model for thinking about how our products perform with customers, we’ve got numbers (or, if you’re more passionate about product & market “feelings,” those can work here, too) that help us prioritize work and make decisions. So useful!

If my product is resonating with a small, but passionate group of early-adopting customers who fit a particular mold, I can do marketing to go after more potential new customers like them, while doing product iteration to better serve and delight a future high-potential group. If I’m very early in the process, I might be marketing and building for only a single, narrow group. But as the product’s adoption grows, that will almost certainly evolve.

Fascinatingly, this model is a far better description of how both ordinary small businesses and extraordinarily high-growth startups have built their products, their markets, and their customer traction. Just read Lenny’s newsletter about product-market fit and you’ll see what I mean.

This model is by no means perfect. But, it can support lots of additions and changes to work for almost any product and organization. If you’re a services business with a consulting practice, you might think swap brand awareness with a more salient metric like “reachable via current network.” If you’re a social, consumer product, maybe you swap conversion rate for signup rate, and ditch brand awareness in favor of average activity/engagement rate.

Even if you’re an investor, you can hypothesize about whether the company can reach the traction it would need to meet your required level of return in a smarter fashion, and holding your models (and the entrepreneurs pitching you) accountable to a less-arbitrary, more customer-centric, and problem-solving process.

We use this mental model at SparkToro—prioritizing the sales and marketing funnel, the onboarding materials, our upcoming case studies, etc. somewhat differently than how we prioritize new product features and more data-gathering. It helps us understand what kinds of customers resonate with various parts of the product, lets us estimate how much opportunity we have in pursuing different paths and making hard-to-figure-out tradeoffs. Plus, we can get this data using surveys, interviews, and analytics—all things we know how to do (honestly, I have no clue how to “feel whether the market is pulling me,” the most common way startups seem to describe their experience with pre-vs-post product-market fit).

In Fairness, There Are Products with Classic “Product-Market Fit“

Whenever I make a passionate argument for an idea or action, I want to be able to back that up by steelmanning (i.e. finding the best form of an opposing argument to test conflicting opinions). In the case of fit-vs.-no-fit, I believe that’s by example. Every VC or tech leader article about the concept points to certain companies and products to back up the idea that fit is real, but rarely achievable, and still worth chasing. Yet every one I could find on the web (seriously, have it, here’s a Google SERP) exemplifies companies whose products are still being refined, and in many cases, have undergone multiple massive overhauls even after they supposedly achieved the mythical “fit.”

So, are there any examples of products that truly match the traditional product-market fit mold? In fairness. Yes. They’re just not talked about in startup world articles on the topic.

Snickers, the candy bar, for example, perfectly matches how tech startup world describes “product-market fit.” The nougaty chocolate concoction has significant market traction and customer engagement. Snickers almost certainly should not change their product. People love it as-is, and as CPG world discovered with New Coke, changing a beloved food product, even a little, is almost always a bad idea. On the other hand, Snickers certainly should test changes to things like positioning, branding, and pricing.

Removing the product’s name from the label was a particularly bold (and surprisingly successful) branding move (via AdWeek)

In this way, the classic candy bar, and (to be fair) many other well-loved, successful consumer packaged goods (especially in food+beverage world, where taste and memory are so inextricably linked) fit the orthodoxy of “Product-Market Fit.”

The best counterpoint I can offer is this: Just because the fit-vs-no-fit model (unintentionally) applies to extremely well-established CPGs does not mean it’s right or useful for early-stage companies, software products, or many other categories. What human beings want from candy bars is not what we want from productivity software or security apps or 3D printers, and we shouldn’t force the model to fit simply because it’s easy or well-established in startup lore.

It’s time to kill the concept of product-market fit, mostly because, like so much of tech startup world’s insular lingo, it was never a good idea in the first place.